Historical overview from the 16th to the 20th century

by Annemarie Schlag

The Protectorate of the Landgrave from the 16th to the 18th century

The Hessian landgraves controlled a protectorate including a Jewish community in Fronhausen. In 1574, during the reign of the Landgrave Ludwig IV of Hesse-Marburg, representatives of the Jews living in his lands signed an agreement that was binding for themselves as well as all other Jews in the protectorate. In this document they swore their allegiance to the landgrave, promising to pay 10,000 Gulden (the current, valid government currency) within twenty months. The signatures on the document include that of Susmann of Fronhausen in his own, Hebraic handwriting.

Susmann’s name is also found in the register of residents living in the county of Lohra and Fronhausen contained in the Salbuch from 1592. The register indicates that the tribute in kind – ½ centner (approx. 25 kg) saltpeter – that Susmann had previously been required to pay had been changed to a monetary one. Furthermore Susmann was required to pay taxes levied for military protection against the Turks. In 1599, the landgrave’s exchequer demanded an increase in required protection tributes. Through perseverance and skilled negotiation, Susmann was able to soften these demands.

Jakob and his wife Sprintze, with five daughters and a son named Seligmann, as well as Hirtz and his wife Brunches are recorded by name in the 17th century. A family named Hirtz with seven children is recorded as living in Fronhausen in 1710. An entry from 1737, records the name Hirsch Levi, aged 68. At that time he had apparently had a letter of protection for living in Fronhausen for 43 years. The name “Hirsch” from 1737 could well be referring to the same Hirtz (with wife Brunches) from the 17th century, as well as having been the bearer of the name “Hirtz” for which the family was named in 1710.

The first records of a growing community are found in the 18th century. All of the families still living in Fronhausen in the 20th century had settled in Fronhausen by this time. Only Jacob Levi is mentioned in the 1744 Register of Jews living in Hesse. He and his wife had four daughters and one son. This son seems to have been Meier Levi (Levit Meier.) He later took on the name Löwenstein. The authorities in Fronhausen created an attest for Löwenstein, certifying that he came from a large family and was the epitome of honesty, making it more preferable to do business with him than with any Christian. Meier Levi (Löwenstein) and his wife had four sons: Jacob, Löb, Hirsch, and Anschel. A daughter named Gütchen, who was born in 1768, was probably also one of their children.

These are the forefathers of the extensively branched Löwenstein family in Fronhausen.

Emancipation and Integration in the 19th century

When the Jews were awarded equal standing as citizens during the rule of Napoleon’s brother Jérôme (1807– 1813), they had to take on family names for identification purposes. Until that time they had always used their given names with their father’s name as a surname.

The following families are recorded as living in Fronhausen in 1852:

Lion Seligmann, merchant, 6 children

Simon Löwenstein, horse dealer

Hirsch Löwenstein, butcher, 11 children

Mendel Löwenstein, butcher, 6 children

Samuel Stilling, butcher, 8 children

Forty-six Jews lived in Fronhausen in 1864. There were two merchants, three artisans, and one horse dealer.

The Jewish Community at the end of the 19th century

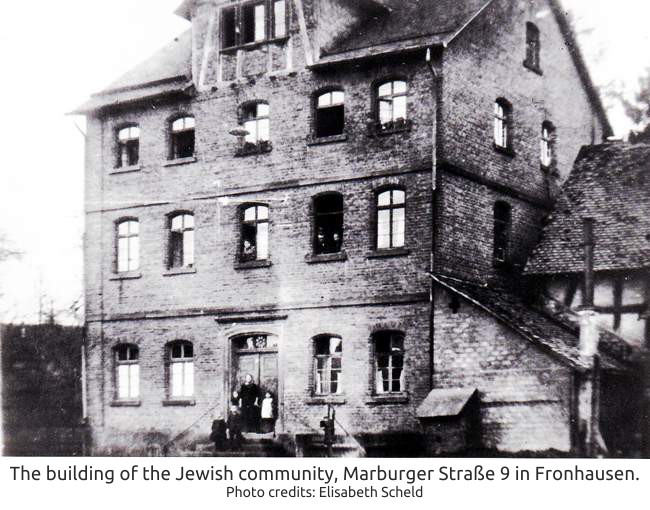

In the 19th century, the Jews of Roth, Fronhausen, and Lohra formed a single worship community with the synagogue located in Roth. In 1881 the Jews of Fronhausen and Lohra left this community to form their own. The worship services and school lessons were held in private homes until a building for these purposes was bought on the street Marburger Straße in 1886. The school was approved in 1883. There were twelve Jewish schoolchildren from Fronhausen and six from Lohra. The first teacher and cantor was Salomon Andorn from Gemünden. He served in this capacity for ten years until 1893, when Jakob Höxter from Zimmersrode took over. Höxter married Franziska Löwenstein, the daughter of Simon and Ester, in 1899. The school seems to have been in existence until the beginning of 1904.

Four non-Jewish families rented the upper floors of the building above the school and the prayer hall. The Hessian-Nassau district office of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich Association of Jews in Germany) took over the building in December 1941.

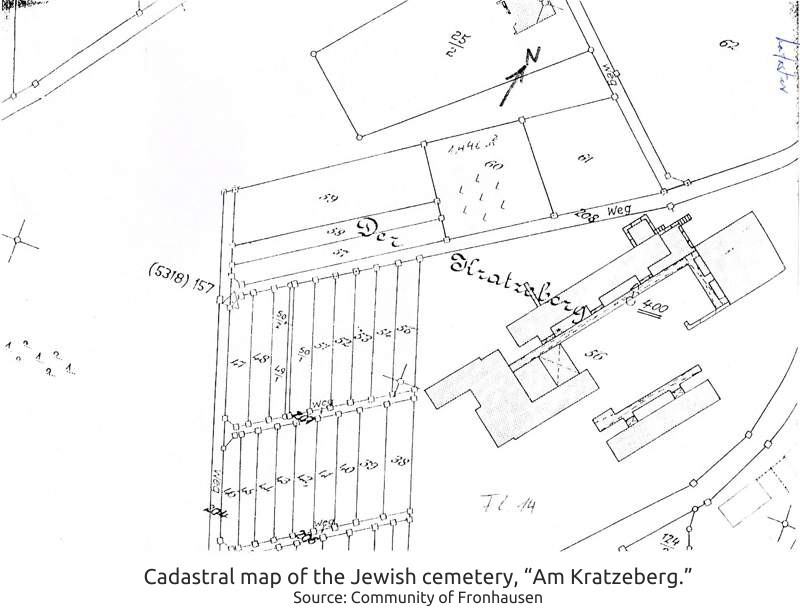

A Jewish cemetery had existed on the mountain Stollberg in an area known as “Am Kratzeberg” since 1874. The owner of the property, the horse dealer Simon Löwenstein, donated it to the Jewish Community for use as a cemetery in 1873.

The Persecution and Extermination of the Jewish Community by the Nazis (1933-1942)

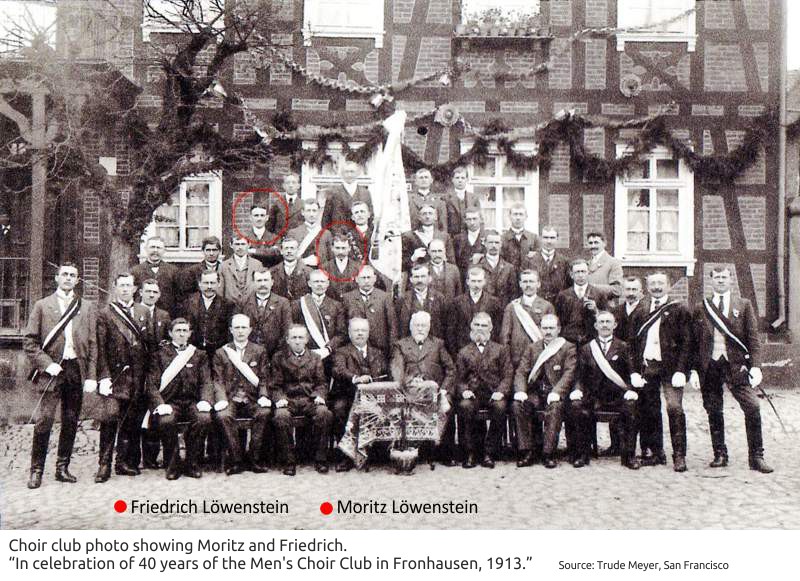

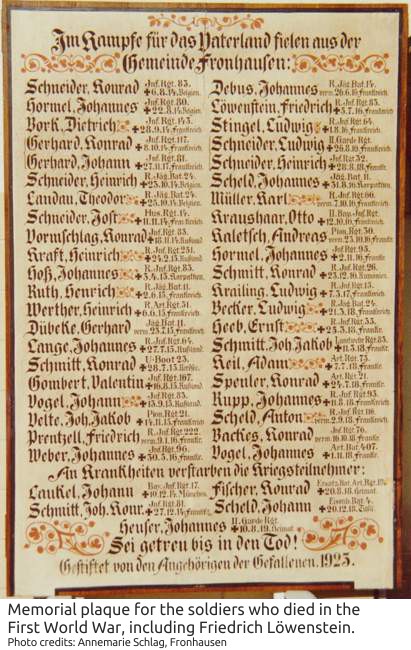

Jews had been living in Fronhausen for many generations. These Germans of Jewish faith were integrated and involved in their village community. The men of the Jewish community served in the military during the First World War. Friedrich Löwenstein, born in 1888, died in the Battle of Verdun.

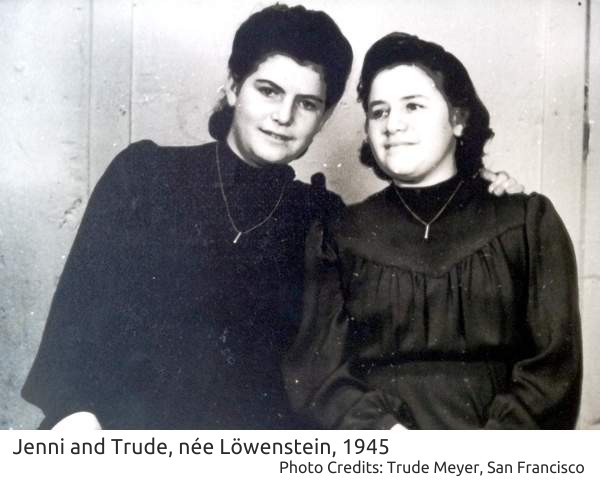

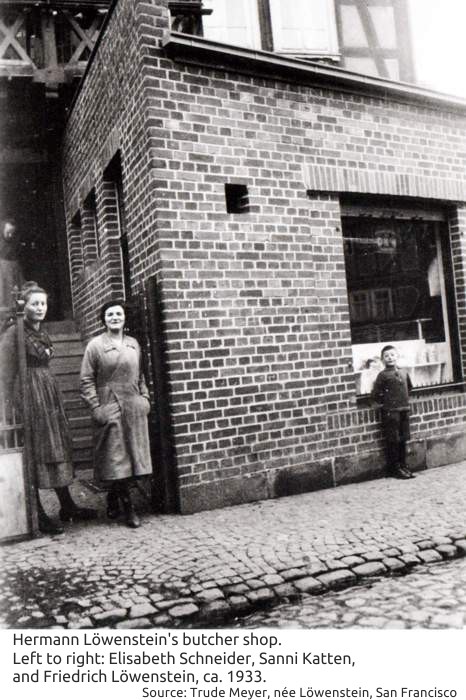

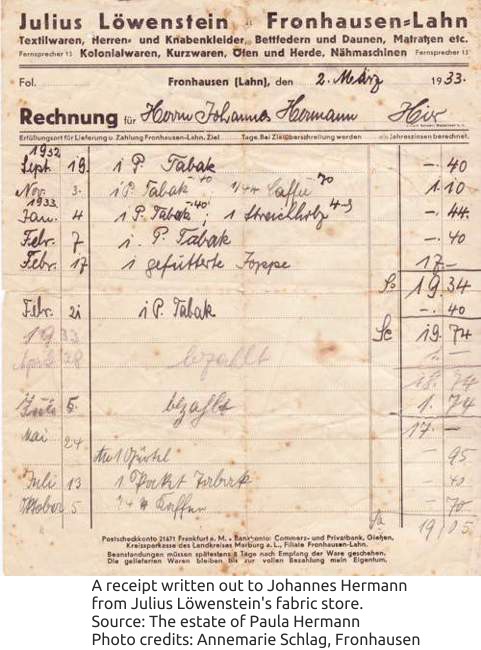

After Hitler came to power on January 30th, 1933, the Jewish population began losing more and more of their rights as citizens. A ban prohibited Hermann Löwenstein from butchering his livestock in a kosher manner as of the end of March 1933. Signs reading “Juden sind hier unerwünscht” (in English: Jews are not wanted here) were posted on the roads going out of the village toward Bellnhausen and Niederwalgern. The display windows of Julius Löwenstein’s fabric store and Hermann Löwenstein’s butcher shop were destroyed in June 1935. The windows of Regina Löwenstein, a widow, were broken in October 1935. Trude Meyer, née Löwenstein, survived the Holocaust. She later described this time: “We thought it was just a terrible nightmare. That we would wake-up and everything would be normal again. We had always lived in a peaceful village. Who had ever experienced any hate? Why should we emigrate, we had never done anyone any harm.”

There were five families living in Fronhausen in 1935: Johanna Bachenheimer, born 1895, unmarried, the daughter of David and Bertha, née Schönfeld. Her parents died in 1922 and 1931. She ran a dry goods (“colonial goods”) store in her house on the street Marburger Straße. There is a German custom that within a village, local people and houses have Dorfnamen: “village” or special names known and used only by the local population. Johanna Bachenheimer’s store was called Bachenheimers. (In this case, the reference seems obvious; however, Dorfnamen are not always easy to decipher, as will be seen below. Buildings have the same name for generations even after the original family name has changed. Also, a second store owned by a Bachenheimer would have to have a different name.)

Gottfried and Frieda Goldschmidt, née Löwenstein, with their son Julius and daughter Ilse.

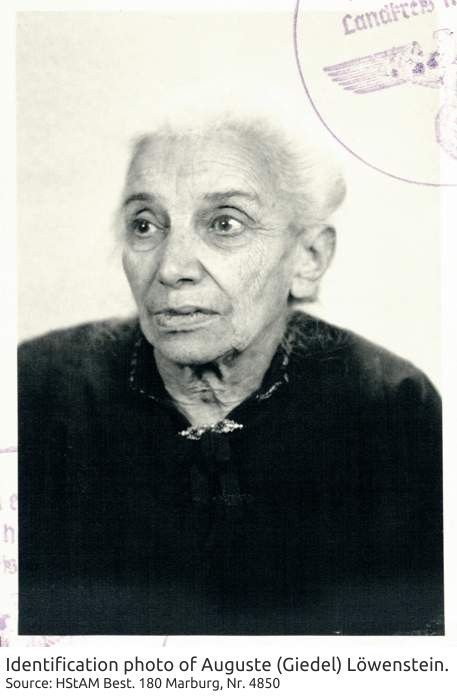

Auguste (Giedel) Löwenstein, born 1868, unmarried, seamstress. She died in 1941. Her place of burial is unknown, she was either buried in the Jewish cemetery in Fronhausen or in the collective graveyard for Jews in Marburg.

Friederike (Rickchen) Löwenstein, born 1872, unmarried, seamstress.

Gottfried Goldschmidt. He was born in Obersemen, and he sold fabrics as a traveling salesman. He lived with his family in the street Gossestraße. The house no longer exists.

Frieda Goldschmidt, born 1894. She was the daughter of Jacob Löwenstein, who lived with his family in Oberwalgern. Auguste (Giedel) and Friederike Löwenstein were Jacob’s sisters. The family’s Dorfname was Isaaks.

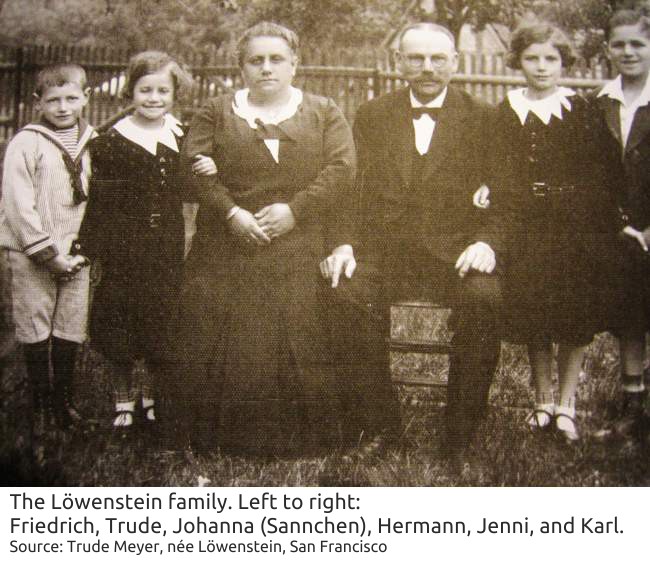

Hermann and Johanna Löwenstein, née Katten from Halsdorf, and their four children: Karl, Jenni, Trude, and Friedrich. The family ran a butcher shop in their house on Stollberg. Hermann also traded in livestock and owned farmlands. He died in Frankfurt after undergoing an operation in 1937. His body is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Fronhausen. Three colleagues attended his funeral: Ruth, Pfeffer, and Schlapp from Bellnhausen. They were denounced because of attending the funeral and thrown out of their trade association. Ruth lost the post office that had been on his property.

Hermann’s parents were Moses II and Dina, née Sonn, from Röllshausen.

Dina’s sister, Minnchen Sonn, lived with her sister and brother-in-law. She died in 1938, and she was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Fronhausen. There is no gravestone for her.

Hermann’s sister Johanna (known as Jette) married Meier Katten II. He was the brother of the Johanna known as Sannchen (see below.)

This Löwenstein family had the Dorfname Hirsche.

Regina Löwenstein, née Rosenbaum, with her daughter Irma and son Hermann. They lived in the street Gießener Straße and traded in skins and furs. Regina’s husband Moritz had died in 1927. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Fronhausen. Moritz was the brother of Hermann Löwenstein. Regina was born in Hochelheim in 1878, to parents Heimann and Minna Rosenbaum, née Hess. The family’s Dorfname in Fronhausen was Moritze. Their daughter Irma married Salli Nathan from Lohra in 1938.

Julius Löwenstein, born 1878, businessman and widower, with his son Otto. His wife, Rosa, née Hammerschlag, from Hannoversch-Münden died in 1928, aged 43. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Fronhausen.

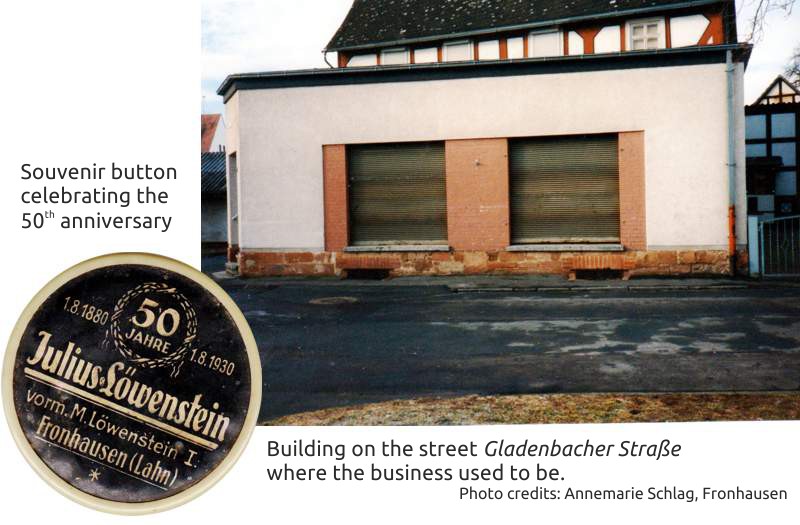

Julius and Otto owned a large fabric store in the street Gladenbacher Straße that had celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1930. Otto married Elfriede Katz from Inheiden in 1940. He then lived with his parents-in-law in Inheiden.

Julius was the son of Moses Löwenstein I. and Henriette, née Schott, the latter from Bad Soden. This family was known in the village as Mendels.

Minna Krug was Julius Löwenstein’s housekeeper. She moved to Felsberg in early March 1938. Sybilla Neuhaus took over for her on August 15th, 1938. Neuhaus was born in 1898, in Westerburg to parents Louis Neuhaus and Henriette, née Hirsch. Her father was a saddle-maker and upholsterer.

The windows of the homes and stores of these Jewish families were destroyed on the evening of November 9th, 1938, as also occurred elsewhere in Germany. The date of this November pogrom is commonly referred to as Kristallnacht or the “Night of Broken Glass” in English. The prayer hall located on Marburger Straße was also attacked. The contents of the hall were destroyed, and many objects belonging to the Jewish community were thrown out into the street.

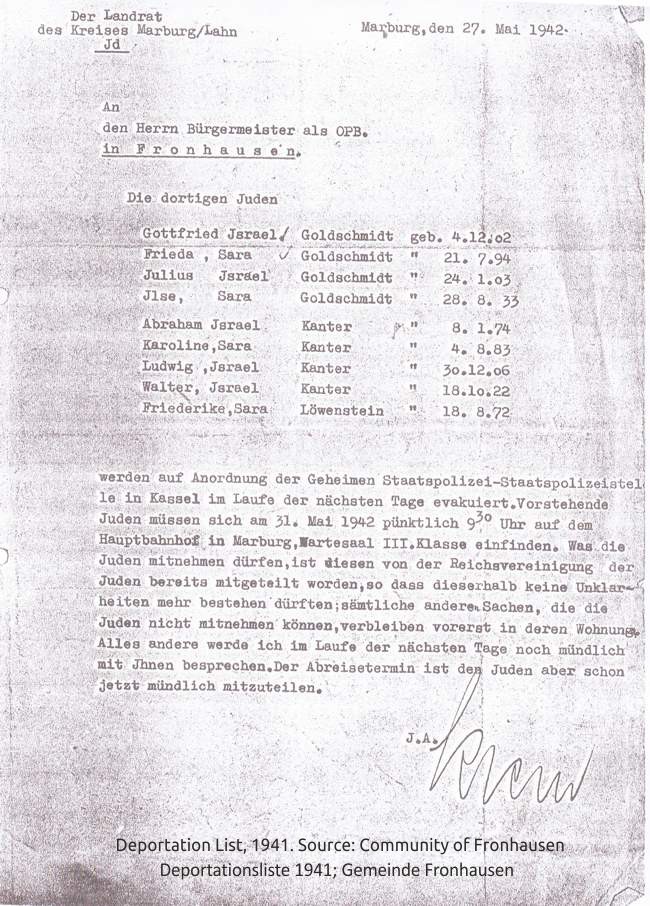

Eleven Jewish people from Neustadt were forcibly resettled into the homes of Johanna (Sannchen) Löwenstein and Gottfried Goldschmidt in May 1941. The resettled persons belonged mainly to two families of the name Kanter. Their first names were Hugo, Moritz, Selma, Abraham, Karoline, née Weinberg, and Ludwig; and Walter, Emanuel, Pauline, and Moses. The eleventh person was Rosa Sachs.

The Jewish population of Fronhausen was eliminated as a result of two deportations from the County Marburg: the first to the ghetto in Riga on December 8th, 1941, the second to Lublin/Sobibor on May 31st, 1942.

The sisters Jenni and Trude Löwenstein were the sole survivors of the people mentioned above. They returned to Fronhausen in 1945. In 1946, they emigrated to relatives in San Francisco who had managed to flee from Halsdorf in January 1941.