From the 16th to the 20th Century

by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

The Protectorate in the 16th - 18th Centuries

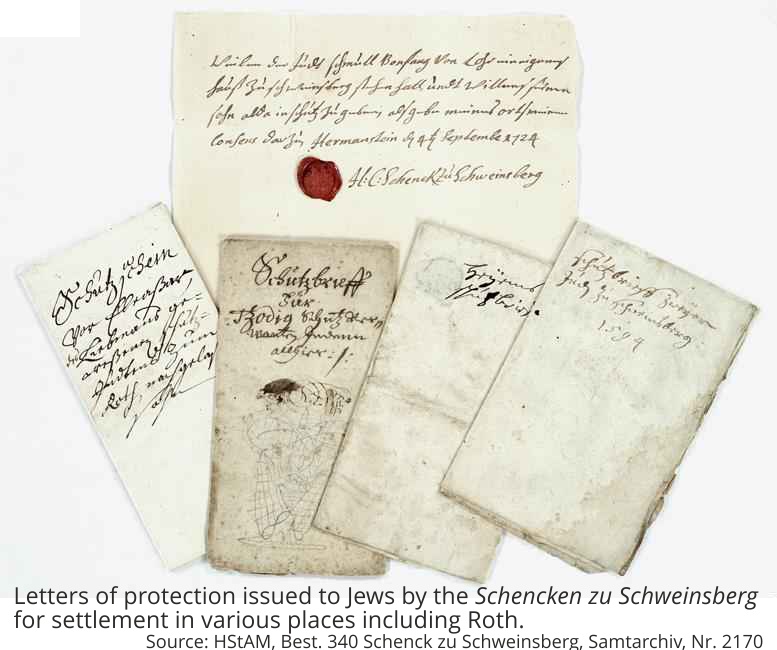

The villages of Roth, Wenkbach, and Argenstein once made up the Schenkisch Eigen, a set of lands under the sovereign control of the noble lineage Schenk zu Schweinsberg. This ancient noble family possessed extensive rights over this territory, including the right to settle Jews on the land. They did this by selling Schutzbriefe (letters of protection) to persons of Jewish faith, a lucrative source of income.

Early evidence of Jews living in the Schenkisch Eigen is found in a 1594/95 register of taxes levied for military protection against the Turks. According to this source, there were seven Jews living in the area who had to pay taxes on property worth 200 Gulden. Each of the seven had to pay 3 ½ Heller for defense against the Turks. It is probable that some of the seven Jews and their families lived in Roth.

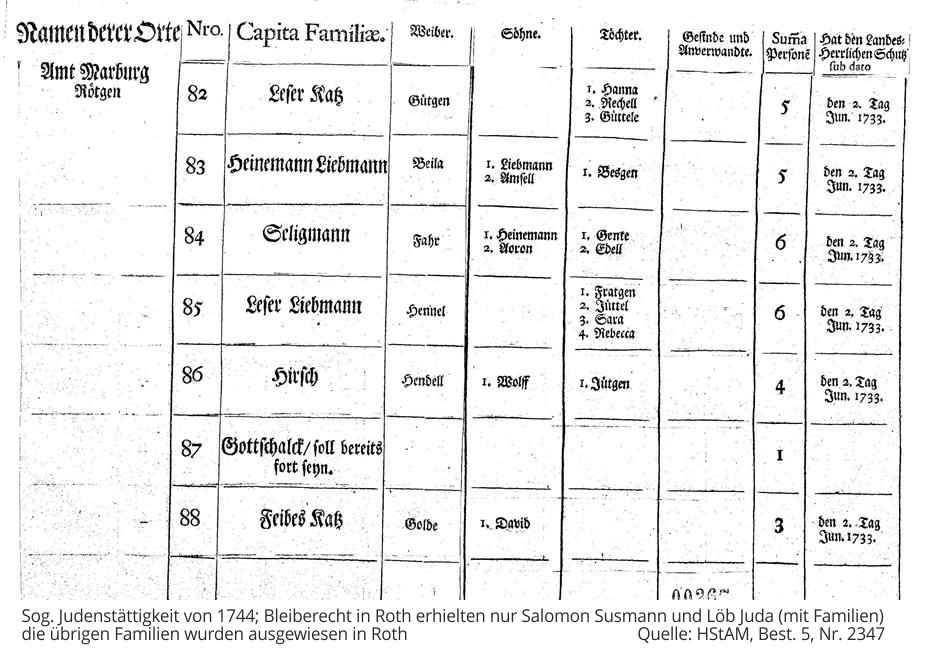

There is definitive evidence from the year 1666 that four Jewish families were living in Roth. In 1710 there were six Jewish families with a total of 33 people. By 1737 the number had grown to 13 families with 54 people. In 1744 the Landgrave of Hesse began to intervene in the settlement of Jews in the villages and towns under his control. He had a register made of all the Jews living in his domain, which included the names of each person in the family. He then decided who would and would not be granted further right of abode in which place. As a result of this action, most of the ca. 38 people (nine families) living in Roth lost their right to live there. Only two families were allowed to stay. After this, the Jewish Community in the area remained very small for several decades.

Emancipation and Integration in the 19th and 20th centuries

It was not until the time of Napoleon’s brother Jérôme’s rule in the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807-1813) that the Jews were first awarded equal standing as citizens. Jews from outside Roth married into the community and paved the way for demographic development in the 19th century. By 1816, a total of four families were again living in Roth: Bergenstein, Höchster, Stern, and Wäscher. By the middle of the century the number of families doubled. The younger sons of the four main families stayed in Roth, and a new family with the surname Nathan arrived in the village. At that time there were about 50 Jews living in Roth, and they made up about 10 percent of the population. By percent Roth had one of the largest Jewish communities in the area around Marburg. When Hitler came to power in 1933, there were still six families in Roth: Bergenstein, Höchster, Nathan, Wäscher, and 3 families with the surname Stern, a total of 32 people.

The Jews of Roth, Fronhausen, and Lohra formed a single worship community in the 19th century. By the middle of the 18th century, they had a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery in Roth.

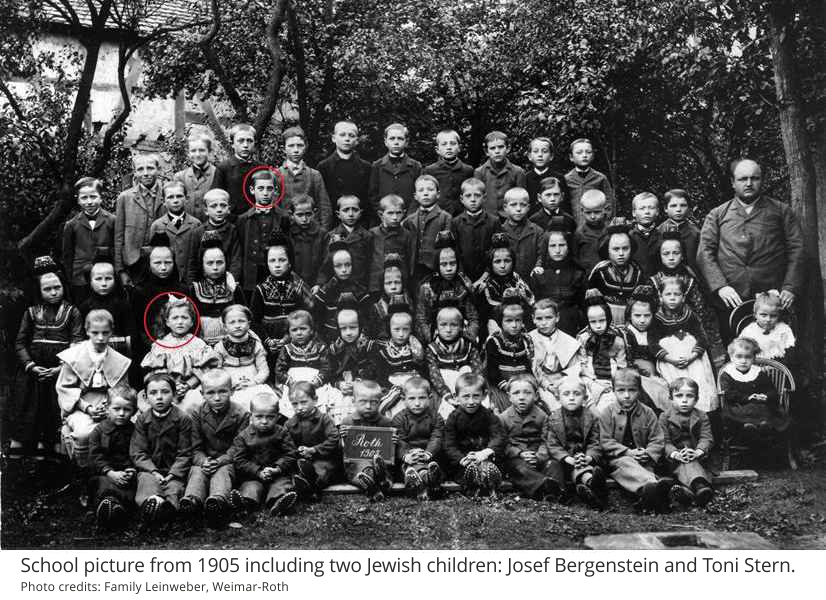

A Jewish elementary school was also established. The schoolteacher usually lived in Roth, but also had to give lessons in Fronhausen for the children from Fronhausen and Lohra. It hasn’t been possible to locate where the school in Roth used to be. The Fronhausen Community split from the larger community in 1881, and bought a building for use as a prayer-house and Jewish school. The Jewish children in Roth began attending the public school at this time.

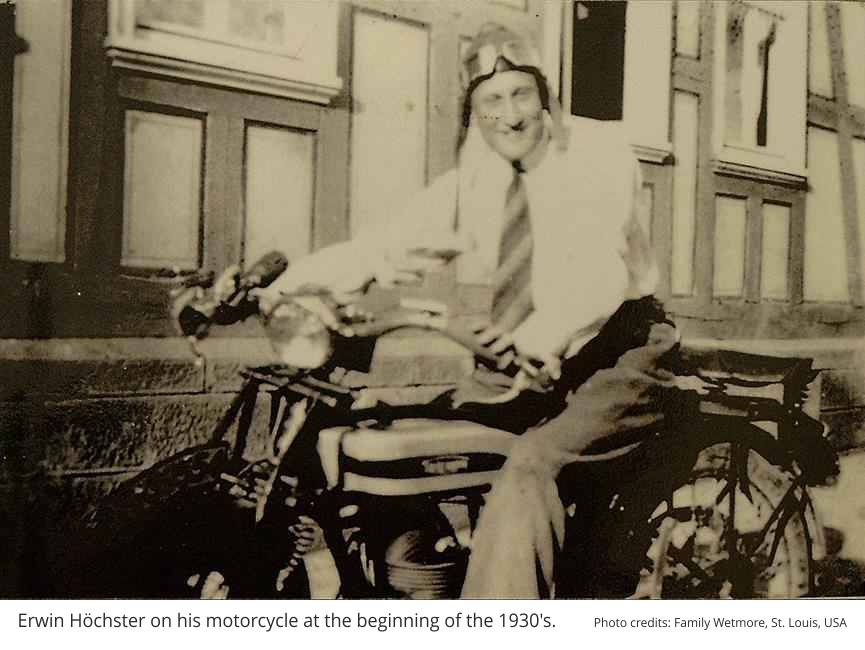

As was typical for Jews in rural areas, the Jews in Roth earned their living through trade, usually dry goods, notions, and fabric or grain and feed, as well as livestock. Well into the 20th century, they traveled the countryside, either by horse and cart, by foot with a Saint Bernard and a small wagon, or eventually by motorcycle, selling their wares. Some Jews owned land and livestock and ran small farms.

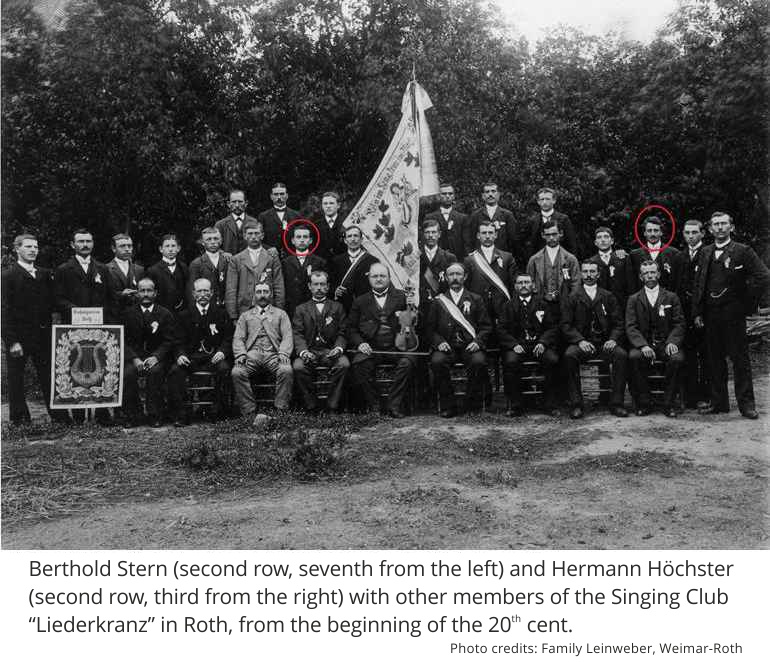

Around the end of the 19th century, members of the Jewish community began joining the local athletic and choir clubs so popular among the general population at this time. There were also Jewish members of the local theater group in Roth. This involvement indicates the extent to which people of Jewish faith were integrated in the village community. Contemporaries bear witness to the positive neighborly relations between Jews and the rest of the population in the 1920’s. Christian and Jewish children played together and formed friendships.

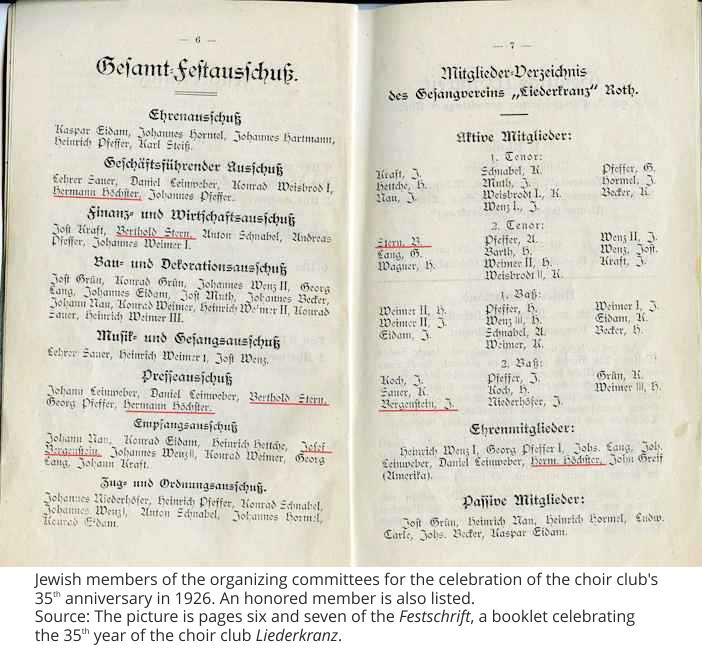

Records of the 35th anniversary of the local choir club, show no evidence of ostracism or exclusion by either side in 1926. The Festschrift, a booklet serving as a memorial document marking the occasion, includes men from several Jewish families as members of the club. Some of these men were involved in the festival committees. Hermann Höchster, the Jewish community elder, is listed as an honored member of the club.

The Persecution and Extermination of the Jewish Community (1933-1942)

The historical election results from the time of the Weimar Republic indicate that Roth was not particularly “brown” - the Nazi Party received fewer votes than the district average between 1928 and 1932. However, the situation changed very quickly after Hitler came to power.

A young mother named Selma Roth died suddenly in 1934. According to members of her family, many villagers attended Selma’s funeral; however, it was only one year later that her widower, the fertilizer dealer Markus Roth, was denounced and accused of criminal behavior in court. Roth’s business collapsed in the aftermath. Signs stating “Juden sind hier unerwünscht” (in English: “Jews are not wanted here”) are documented as having been on a business property and on a farm at this time.

Survivors report of nasty pranks and of being excluded from play at school after the Christian children joined the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) and the Bund deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls: the girls’ branch of the Hitler Youth.) Adult Christians began avoiding their Jewish friends and neighbors. Jewish men were not allowed to work and thus could no longer support their families. Jewish families began to see that there was no future for them in Germany. They tried to flee, but not all of them had the financial means and necessary contacts to emigrate. Some members of the Höchster, Roth, and Stern families managed to escape between 1936 and 1938, but only one of the two Stern families was able to flee as a complete unit. Eleven Jews from Roth survived in South Africa, the USA, and in England.

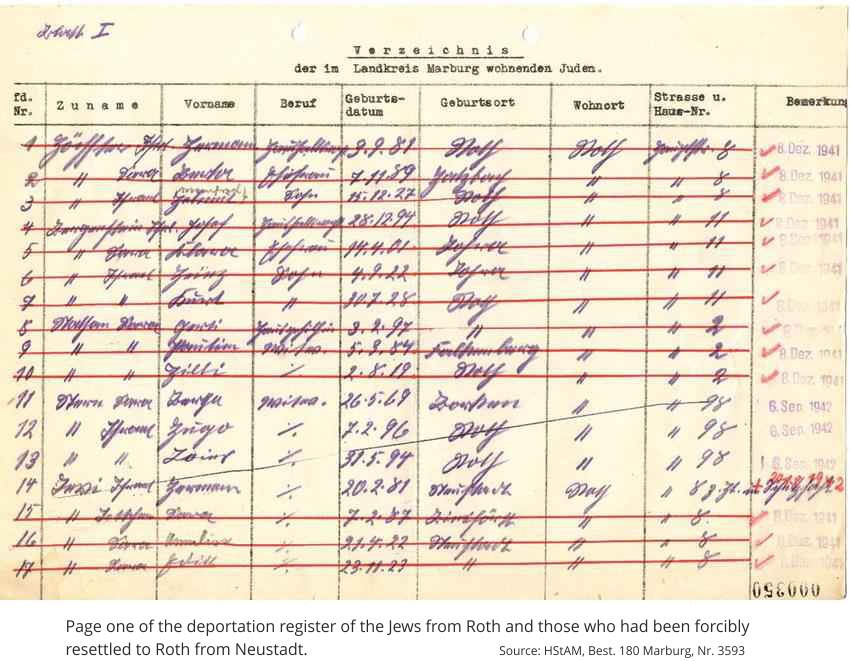

For those left behind, life became increasingly difficult as laws and regulations became stricter and economic hardships ever more pressing. To make matters worse, Roth served as a ghetto village in the summer of 1941. At that time, many Jews were forcibly concentrated into single houses in the cities and centralized places in the countryside. Twenty Jews from Neustadt were forced to moved into living quarters with the remaining members of the Bergenstein, Höchster, Nathan, and Stern families. They lived there in terribly tight conditions. Some of the Jews were deported to Riga in December 1941, the rest were deported to Theresienstadt in September 1942. None of the Jews from Roth survived the ghettos and the concentration camps.

Jewish life in Roth was thus completely exterminated.