by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

The oldest record of a synagogue in Roth is found in the cadastre from 1773. According to this source, a Jew named Levi owned a house, which was extended to create a Jewish school. A glance at the relevant cadastral map, itself dating to 1766 or 1769, shows an elongated, continuous building on that site. The Jewish school was obviously privately owned.

The home and the synagogue burned down in the fall of 1832. The property owner, Herz Stern, bought a sizable farmstead somewhere else in the village and left the first property to the Jewish Community as a site for a new synagogue. By November 1833, the blueprints for a new building were prepared, the construction jobs had been assigned, and the necessary funds had been collected. The exact date of completion is unknown; however, a disagreement about the allocation of prayer space in the synagogue dates to the fall of 1838, so construction must have been completed by this time. There is no reason to believe that this small building, which must have been relatively simple to erect, would have taken five years to finish.

The building still stands today.

The synagogue has a nearly square floor plan. The half-timber style architecture (German: Fachwerkkonstruktion) is built on a sandstone foundation with a hipped roof.

The south and west-facing walls were shingled with slate, while the north and east-facing walls were rendered with plaster. The walls of the north, south, and east-facing walls are marked by high, round-arched windows. The architectural style of this simple, clearly structured building is classical. The main entrance to the building was on the west side. Women entered the building using a steep outer staircase leading to a gallery held up by two columns.

The Torah shrine (almemar or almemor) was located inside the building in front of the east wall.

The pews were arranged with an aisle in the middle facing towards the east. The lectern (bema or bima) stood in the middle of the room in front of the Torah shrine.

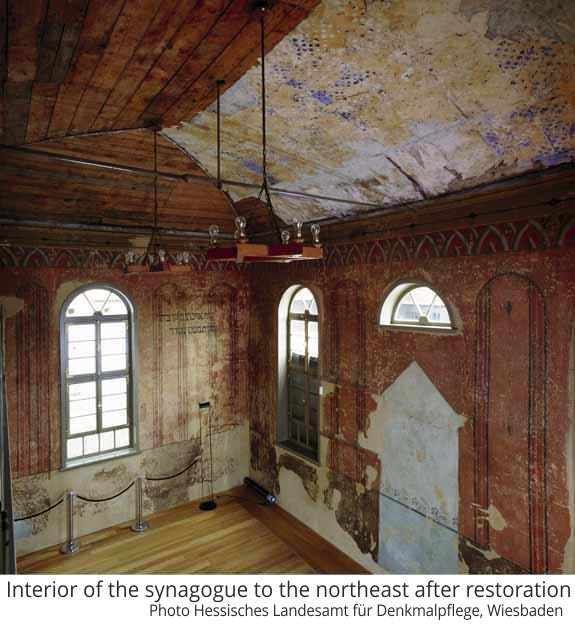

The barrel-vaulted ceiling of the synagogue is rounded on the ends, similar to a cloister-vaulted ceiling, but with an elongated center line. The blue painted background with golden stars is only visible in a few remaining segments. The two lamps in the shape of the Star of David that are currently hanging in the synagogue are not originals, but there originally were two chandeliers hanging from the ceiling as well as further lamps installed on the walls.

The walls were colored reddish-brown with arch-like decorations. There was an inscription in the Hebrew language on each of the north and side walls. The arches and the inscriptions were gilt-bronze, which has now oxidized to black. A translation of the Hebrew inscription of Psalm 26:8 on the north wall can be given as “LORD, I love the habitation of Thy house, and the place where Thy glory dwelleth.”

The inscription of Leviticus 19:18 on the south wall as “thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” (The Torah translations into English are taken from https://www.mechon-mamre.org/.)

Remnants of a light blue background color on the walls with a floral frieze can best be seen where the Torah shrine had been. The remaining color seems to be in the art déco style and can be dated to the 1920’s. Beneath this layer are murals in the art nouveau style that must be from the turn of the 20th century. There seem to be no traces of paint from the time of construction.

In November 1938, the State of Hesse served as a sort of testing ground for the pogrom that quickly spread to the entire German Reich. The pogrom actually began on November 7th in several places in Northern Hesse. This was the same day that Herschel Grynszpan assassinated the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris. The Nazis used this incident to trigger the so-called Ausbruch des Volkszorns (in English: eruption of the people’s wrath) that led to the staging of Kristallnacht, often translated into English as “The Night of Broken Glass” on the night of November 9th, 1938. The pogrom continued for three days.

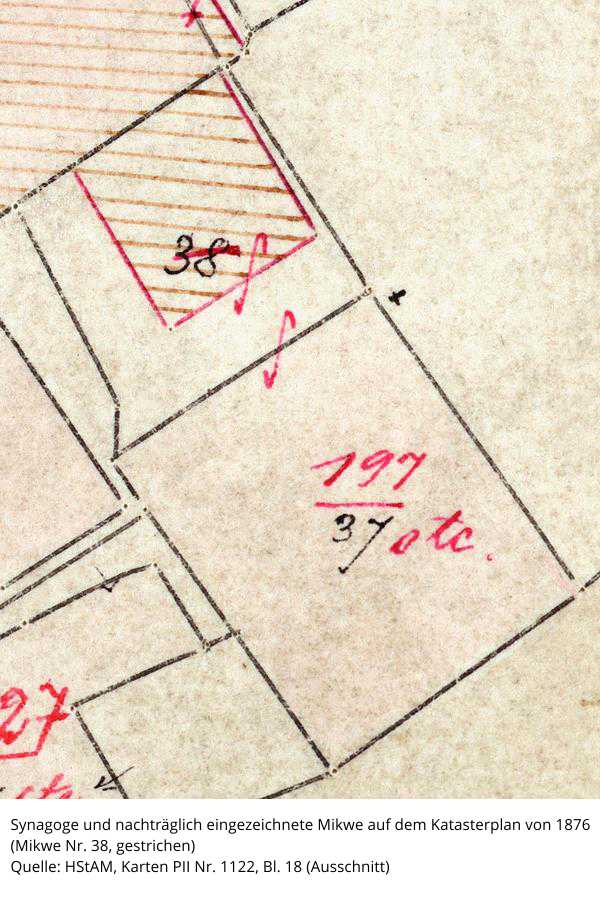

Like other places in the district of Marburg, Roth joined in the pogrom early. Sturmabteilung (SA) members from various places, including people from Roth, destroyed the synagogue in Roth on the evening of November 8th. Concern for the neighboring farm buildings prevented them from setting the synagogue on fire; however, the entire interior was destroyed and the pillars supporting the women’s gallery were attacked with axes and pulled out of position. The Jewish community was forced to sell the synagogue and the grounds including the mikveh to two adjoining neighbors on February 9th, 1939. The mikveh was torn down in 1957, and the synagogue was used as a granary. With financial assistance from the District Marburg-Biedenkopf, Weimar Township bought the building and the property in 1990. In 1995 the District acquired the property for the symbolic price of 1 Deutsche Mark.

In 2023, the working group was able to create a virtual reconstruction of the synagogue with financial support from the Hessian Ministry of Science and Art:

Screenshots: reconstruction in the 20´s and reconstruction around 1900; ©ArchitecturaVirtualis GmbH

by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

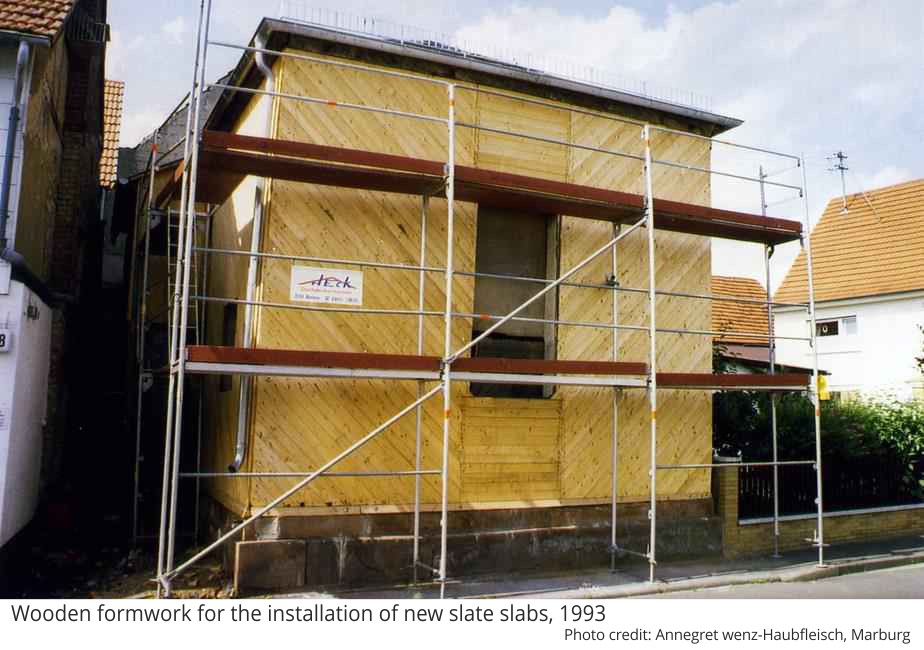

First plans for restoring the synagogue materialized in the 1980’s. The Weimar Township commissioned an assessment of the existing structure at the end of 1988. This assessment included a description of the state of the building as well as of material damages, which were thoroughly documented in photographs and blueprints. The assessor also provided a cost estimate for restoring the building. In the summer of 1990 the township bought the building. The restoration of the outer walls didn’t begin until 1993 and took two years.

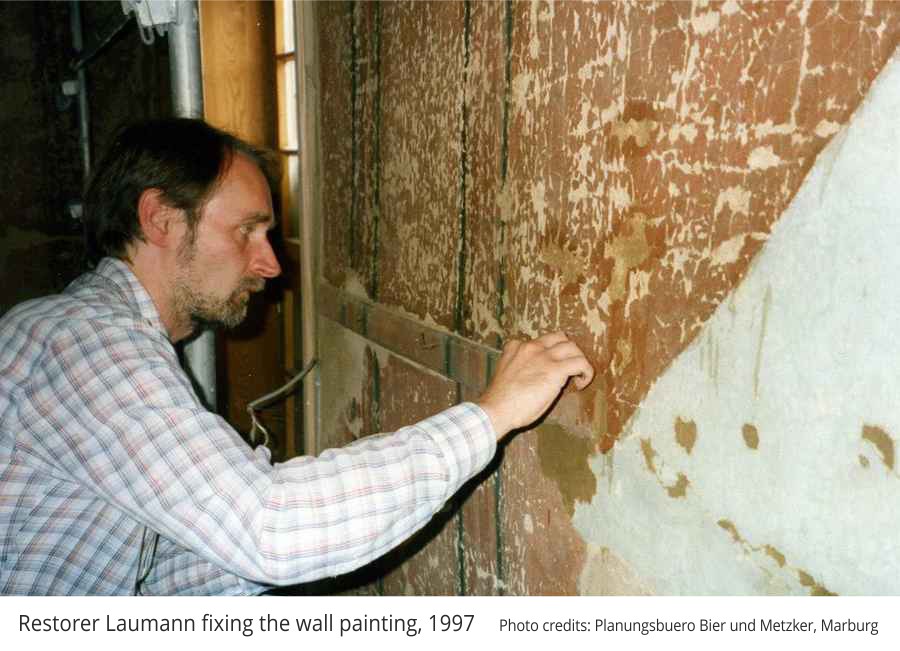

The load-bearing structure was secured, a new roof was put on, the windows and doors were replaced, and the slate shingles on the outer walls were renewed. The walls with plaster facing were newly rendered. There was then a pause in the renovations for several years. Following purchase of the building by the District of Marburg-Biedenkopf in 1995, the restoration of the interior of the building was completed in 1997. The concept behind these efforts is perhaps a bit unusual. Instead of restoring or recreating a previous state of the building, the current appearance of the building was preserved. Only structural damages such as those caused by mice in the lower parts of the walls were repaired. The murals were merely fixated in their current state. Conservator-restorers touched-up the inscriptions to improve readability; however, they had to remove much of the starry sky hanging down in torn fragments from the ceiling. Only the parts that were still attached could be restored easily. The loss of the ceiling mural certainly detracted the most from the charm of the interior, but this loss couldn’t be helped after the delay of nearly ten years following the cost estimate. A new railing was added to secure the women’s gallery, making it accessible. The two lamps in the form of the star of David were saved from a Christian church and installed in the synagogue.

The specialist for the conservation of monuments who was responsible for this project, Dr. Michael Neumann, designed this concept of preservation for the synagogue in Roth in order to create a “document of the moment.” The intention is not only to preserve the synagogue, but also the moment of destruction as a warning memorial for future generations. In clarifying this concept, Dr. Neumann spoke of the need to create “spaces for reflecting” (German: Denkräume.) Indeed, upon entering the synagogue, the eye immediately notices the traces of violence, but at the same time is caught up by the simple beauty of the room. The unsettling feeling that naturally arises when confronted with this contradiction drives the viewer to assess and analyze his or her reaction, thus promoting dialogue and discussion.

The restored synagogue was reopened on March 10th, 1998, with a special ceremony attended by many survivors and their children and grandchildren from the USA.

Photo credits: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Nr. 414.895 www.fotomarburg.de

by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

A mikveh is a central part of every synagogue. The water used for the ritual cleansing must be “living” water, meaning water from a natural source such as groundwater, spring water, or rainwater. There are certain rules and procedures determining how this water is added to the bath.

There are also traditional rules for both men and for women as to how and when the mikveh ritual should be carried out. This serves the purpose of ritual cleansing, in order to become – using a Yiddish term – kosher. Orthodox Jewish men are encouraged to visit the mikveh before each sabbath as well as before the Day of Atonement Yom Kippur. Women should visit the mikveh after menstruation, on the eve of their wedding day, and after giving birth. Additionally, Jews are required to take an immersion bath after coming into contact with a dead person because death is linked to uncleanness. A ritual cleansing known as “Kaschern” is also suggested for new dinnerware and porcelain.

There is no record of the mikveh in Roth until 1910. However, the structure was likely much older because it was replaced with a new building in 1916.

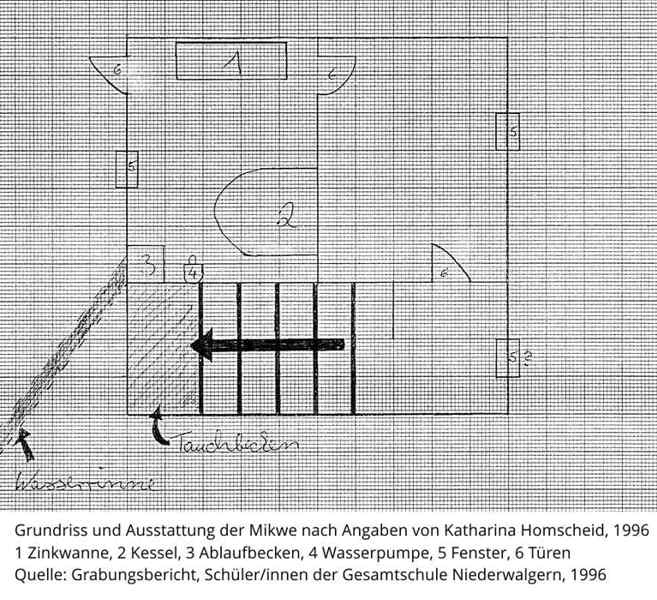

According to the testimonies of contemporaries, there was a pump, a kettle, and a bathtub in the small building. These are typical utensils for the pre-cleansing, carried out before going down several steps into the mikveh, where the actual ritual cleansing took place in a basin filled with groundwater.

In the summer of 1996, part of the foundations and the stairs to the immersion bath were uncovered as part of an excavation project by the comprehensive school in Niederwalgern. This project was overseen by employees of the Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege (Hessian State Office for Monument Protection) in Marburg. For structural reasons they chose not to dig down to the groundwater table. The process was documented, and the excavation site was then refilled.

In 2004, students from the Niederwalgern Comprehensive School, under the direction of Gabriele C. Schmitt, created a mosaic for the courtyard of the synagogue, the site of the mikvah.