by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

Nameless Jewish inhabitants of Schenkisch Eigen, an area including the villages of Roth, Wenkbach, and Argenstein, are first recorded in 1594-95. We do find records of family names in the 17th century, but their settlements were apparently not continuous. The ancestors of the Jews living in Roth in the 20th century can first be identified beginning in the 18th century.

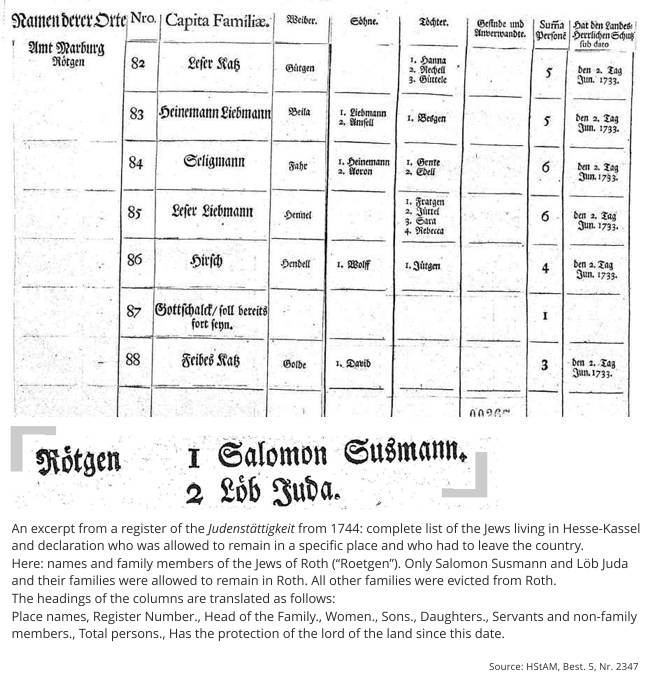

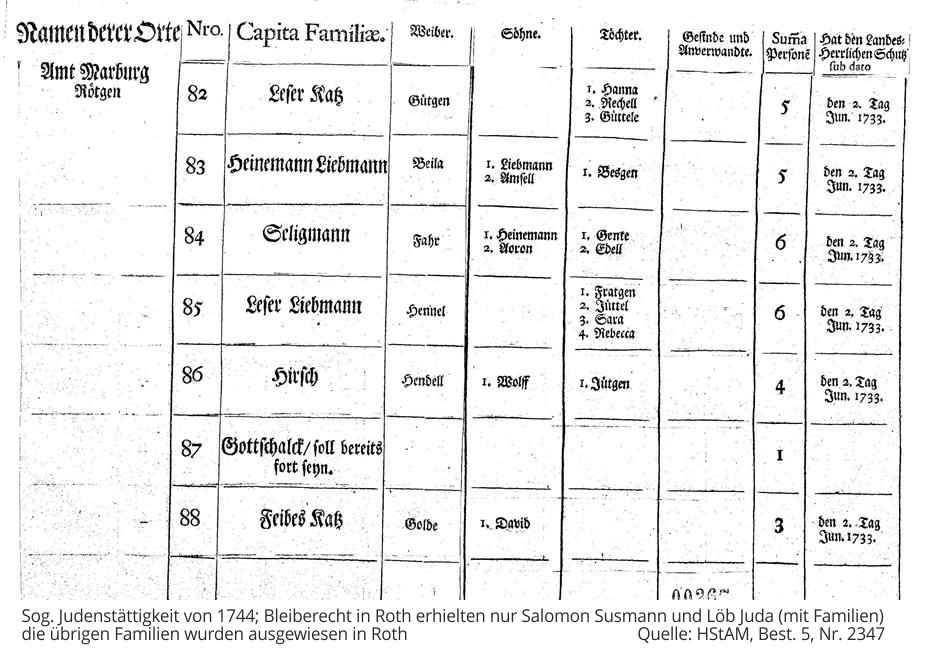

Of the nine Jewish families living in Roth in 1744, only the families of Salomon Susmann and Loeb Juda (also known as Loeb Salomon) received rights to continue living in the village. There is no further record of the Salomon Susmann’s family, and Loeb Juda’s family name died out without a male heir at the end of the 18th century.

A son of the evicted Seligmann family, Aron Seligmann, apparently either stayed in the village or returned to it later. He and his wife Scheile were childless, so they adopted a nephew (the son of Scheile’s sister) from Breidenbach in the Grand Duchy of Darmstadt. During the Westphalian Period, from 1806-1813, this nephew took on the name Stern and became the forefather of the three Stern families still living in Roth in the 20th century.

The founder of the Höchster/Höxter line, which also existed into the 20th century in Roth, was Meyer Isaac. He was Swabian by birth and moved to Roth from the County of Wittgenstein with his wife in 1775. His wife, whose name we do not know, was a sister of Aron Seligmann who had been working there as a servant. Meyer Isaac was granted a residence permit – a document known in German as a Toleranzschein, lit. a certificate of tolerance. They had three children: Sara, Reitz, and Isaac. Isaac took on the name Höchster.

Isaac’s sisters married men who permanently settled in Roth from elsewhere. Reitz married Seligmann Bergenstein from Leihgestern. He had worked in Roth as a servant. Sara wedded Marcus Waescher from Ziegenhain, who moved to Roth in 1815. The latter family-line died out the end of the 19th century.

In the first half of the 19th century two daughters of the Stern family married two sons from the Höchster family, with the result that all Jewish families in Roth were blood-relatives.

The widowed Giedel Höchster, née Stern, married Baruch Nathan from Lohra in 1855, thus establishing the Nathan family in Roth.

The family lines of Stern, Höchster, Bergenstein, and Nathan were the basis of the Jewish community in Roth from the 19th century onward. Markus Roth from Nieder-Ohmen married into the family of Herz Stern II in 1922. This Stern family’s only son Hermann died in the First World War. Markus Roth started a family with the Sterns’ daughter Selma.

In the 20th century, nine Jewish families and a single person from the Bergenstein family lived in Roth.

The development that took place in the 20th century is almost incomprehensible despite all the academic research on National Socialism. Roth was not one of the particularly “brown” places before 1933. An analysis of the Reichstag election results of the Weimar Republic shows that although the people of Roth had strong German nationalist leanings, many also tended towards the SPD and the KPD. The remaining few were distributed among the liberal parties. In the Reichstag elections from 1928 to 1932, the NSDAP in Roth was well below the district average. It is fitting that as late as 1934, many residents took part in the sudden death of the young mother Selma Roth and paid their last respects.

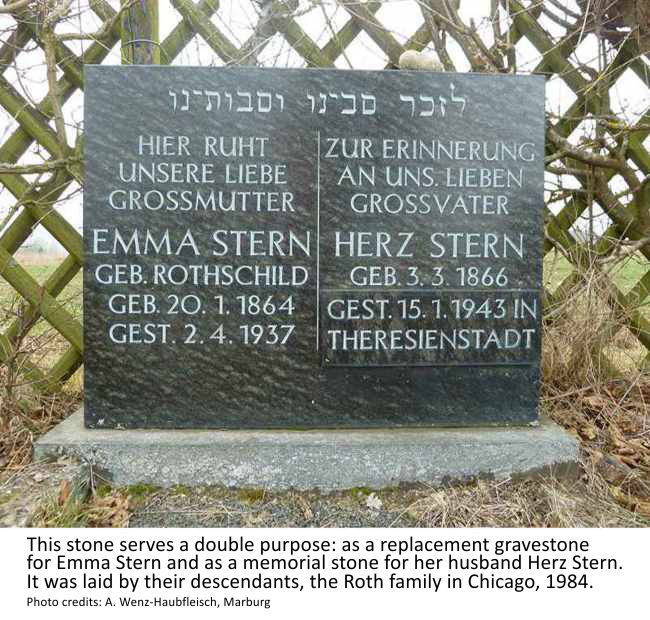

By 1935, the situation had already changed considerably. It is on record that there were signs on the premises of a businessman and on a farm saying “Jews are not wanted here”. Markus Roth, the fertilizer dealer, was accused of breaking the law in court and denounced in the press, whereupon his business practically came to a standstill. When Emma Stern, Roth's mother-in-law, died in 1937, no Christian resident accompanied her to the cemetery, and the Jews, who were untrained in the trade, even had to make the coffin themselves.

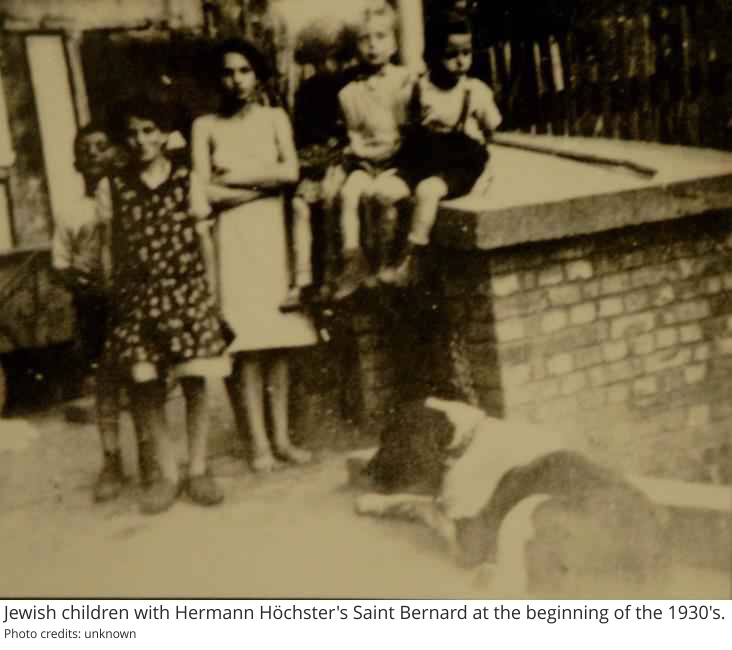

The Jewish children's former playmates joined the Hitler Youth, were indoctrinated with National Socialist propaganda and turned their backs on them. They were isolated as a result, their everyday lives became dull and dreary. At the Roth elementary school, one of the two teachers, Knott, was a convinced National Socialist who bombarded the children with diatribes against Jews and humiliated the Jewish pupils all the more. However, they were only able to attend the school until around 1937 anyway.

Perhaps the Jewish families did not immediately realize that their lives were under threat. In any case, from the mid-1930s they realized that they could no longer maintain their economic existence and that they and their children no longer had a future in Germany. So they tried to leave the country. Not all of them had the financial means or the necessary connections. For the Bergenstein and Nathan families, it was probably hopeless from the outset. Some of the Höchster, Roth and Stern families made it out, but only one of the Stern families was able to flee to safety. Eleven Jewish residents of Roth survived in South Africa, the USA and England.

Life became increasingly difficult for those who stayed behind as the laws and regulations became more and more rigid and the economic hardship more and more pressing. A few courageous villagers secretly sent them food.

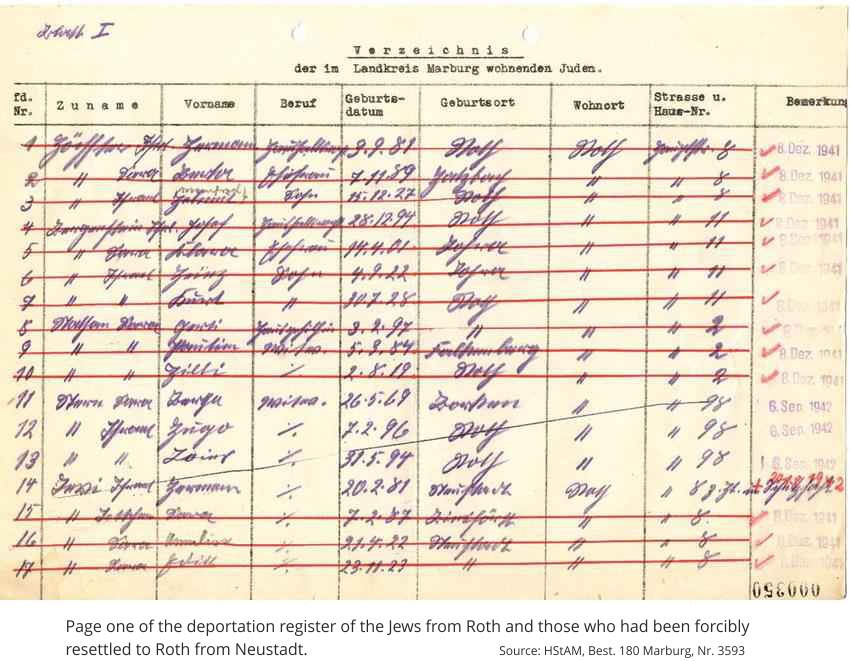

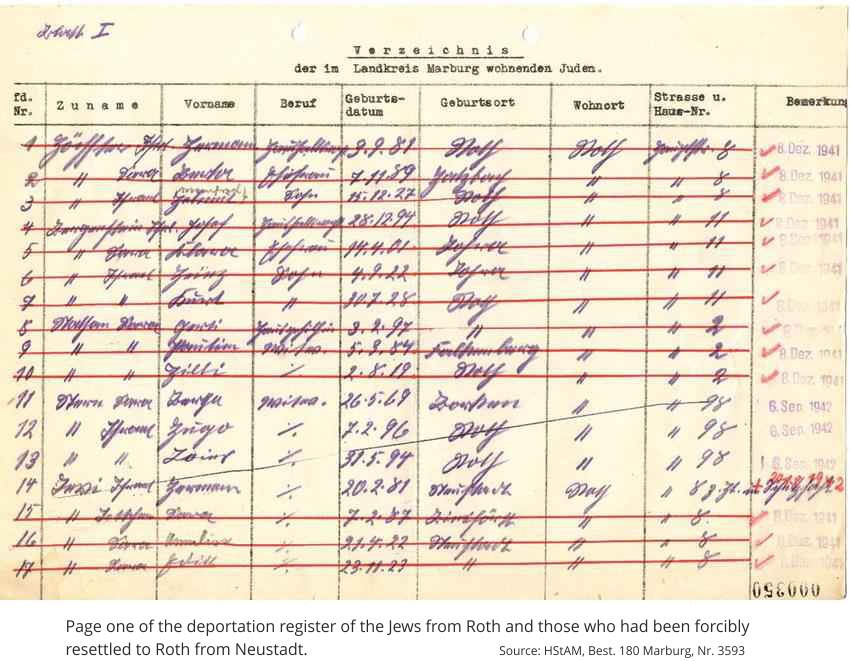

In the summer of 1941, Roth became a ghetto village. 20 people from Neustadt were forcibly quartered in Jewish families, ten of them with the Höchster family alone, six with the Sterns and two each with the Nathans and Bergensteins. After the first deportation to Riga in December 1941, to which most of the people fell victim, some of them stayed behind in the homes of Roth families. They were deported to Theresienstadt together with the last Stern family in 1942. There were a total of three deportations in the administrative district of Kassel, although there were no Roth Jews on the middle transport to the district of Lublin (Izbica/Sobibor) at the end of May 1942.

15 Jews from Roth were killed in concentration camps. In just a few years, Roth had developed from a “friendly, quiet” village into a nasty, inhumane and inhumane place for the Jews living in the immediate vicinity due to the actions of convinced National Socialists.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version). The section “Jewish families in the 20th century” is taken from the brochure: Memorial Stones - "Stolpersteine". To those Jewish families who were expelled from Roth to other countries or deported and murdered during the Nazi era, the working group has dedicated stumbling blocks and this commemorative brochure with in-depth biographical information to 2010 and 2013.

Last Update: April 9th, 2015

An abundance of sources on the history of the Jewish communities in both of these villages can be found in the Hessian State Archives in Marburg and the Main Hessian State Archives in Wiesbaden, including, for instance, 18th century birth, marriage, and death certificates and official reparation records, as well as in the archives of the Community of Weimar (Lahn). (The Community of Fronhausen does not maintain a public archive.

The following list is limited to literature that explicitly deals with one or both of these communities. Only a few titles are included to provide a supplementary overview, as they are highly relevant for the specific topic at hand.

ALTARAS, Thea: Synagogen und jüdische Rituelle Tauchbäder in Hessen - Was geschah seit 1945? Aus dem Nachlass hrsg. von Gabriele Klempert und Hans-Curt Köster, 2. Aufl. Königstein 2007

ARNDT, Steffen: Kaiserliche Privilegien versus landesherrliche Superiorität im 18. Jahrhundert. Das Beispiel der Familien Schenck zu Schweinsberg und Riedesel zu Eisenbach, in: Zeitschrift des Vereins für Hessische Geschichte und Landeskunde 111, 2006, S. 127-152 (zum Streit um die Schutzherrschaft über Juden)

ARNSBERG, Paul: Die jüdischen Gemeinden in Hessen. Anfang, Untergang, Neubeginn, Bde. 1-2, Darmstadt 1971, Bd. 3 (Bilder, Dokumente), Darmstadt 1973

Bachmann, Ewald: Das Prinzip Hoffnung. Drei ehemaligen Synagogen im Landkreis Marburg-Biedenkopf, in: Spirita. Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft, Jg. 3, 1989, Januar-Heft, S. 48-51

Becker, Siegfried: Konversion des Juden Feist von Roth 1755, in: Heimatwelt (Weimar/Lahn) H. 40, 2005, S. 26-30

Becker, Siegfried: Halwaja. Hamet. Erinnern an die Opfer der Shoah als Beschreibung der zerbrochenen Zeit. Vortrag anlässlich der Feier zum 10-jährigen Jubiläum des Arbeitskreises Landsynagoge Roth, 11. Juni 2006, in: Heimatwelt (Weimar/Lahn), H. 41, 2006, S. 30-33

Becker, Siegfried: Die Rechtsformel des Judeneids im Schenkisch Eigen, in: Heimatwelt (Weimar/Lahn), H. 43, 2008, S. 25-35

Becker, Siegfried: Artikel in der Chronik Von Essen nach Hessen. 850 Jahre Fronhausen 1159-2009, hrsg. von der Gemeinde Fronhausen, red. Renate Hildebrandt, Friedrich von Petersdorff und Siegfried Becker, Fronhausen 2009: Salpeterzins des Juden Susmann, S. 279-286; Ein Konflikt um das Ortsbürgerrecht der Juden im Vormärz, S. 325-332

Bibliographie zur Geschichte der Juden in Hessen, bearb. v. Ulrich Eisenbach, Hartmut Heinemann und Susanne Walther (Schriften der Kommission für die Geschichte der Juden in Hessen, Bd. XII), Wiesbaden 1992

Buch der Erinnerung. Die ins Baltikum deportierten deutschen, österreichischen und tschechoslowakischen Juden, bearb. v. Wolfgang Scheffler und Diana Schulle, hrsg. v. Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. und dem Riga-Komitee der deutschen Städte gemeinsam mit der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin – Centrum Judaicum und der Gedenkstätte Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz, 2 Bde., München 2003

Degen, Paulina / Iris Jargon / Melanie Wenz: "Vergangenheiten, die nicht aufhören wollen" (Amos Os) / der jüdische Friedhof in Roth, in: Experiment. Zeitung der Elisabethschule, Marburg, Nr. 11: Februar 1994, S. 28-38

Demandt, Karl E.: Die hessische Judenstättigkeit von 1744, in: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 23, 1973, S. 292-332

Die ehemaligen Synagogen im Landkreis Marburg-Biedenkopf, hrsg. v. Kreisausschuß des Landkreises Marburg-Biedenkopf, red. Ulrich Klein, Marburg 1999 (zu Fronhausen, S. 19-29, zu Roth S. 103-113)

Händler-Lachmann, Barbara: Jüdische Friedhöfe und Synagogen, in: Kulturführer Marburg-Biedenkopf. Ausschnitte aus der kulturhistorischen Vielfalt eines Landkreises. Hrsg. vom Kreisausschuß des Landkreises Marburg-Biedenkopf. 2., überarb. Aufl. 1995, S. 137-145

Händler-Lachmann, Barbara / Ulrich Schütt: „unbekannt verzogen“ oder „weggemacht“. Schicksale der Juden im alten Landkreis Marburg 1933-1945, Marburg 1992

Händler-Lachmann, Barbara / Harald Händler / Ulrich Schütt: ,Purim, Purim, ihre liebe Leut, wißt ihr was Purim bedeut‘? Jüdisches Leben im Landkreis Marburg im 20. Jahrhundert, Marburg 1995.

Haubfleisch, Dietmar: Ehemalige Landsynagoge Roth, in: GedenkstättenRundbrief Nr. 95, 6/2000, S. 37

Höck, Alfred: Grabinschrift einer jüdischen Frau. Ein ehrenvoller Nachruf für Esther Löwenstein / Auf dem Friedhof von Roth, in: Hessenland, Jg. 15, 1967, Folge 13, o.S.

Höck, Alfred: Juden im Marburger und Kirchhainer Gebiet nach einer Übersicht aus dem Jahre 1838, in: Heimatjahrbuch 1979 - Kreis Marburg-Biedenkopf, S. 144-146.

Höck, Alfred: Zur Geschichte der Juden in Roth (Weimar, OT Roth), Ms. o.J. ca. 1986

Jüdische Geschichte in Hessen erforschen. Ein Wegweiser zu Archiven, Forschungsstätten und Hilfsmitteln, bearb. von Bernhard Post (Schriften der Kommission für die Geschichte der Juden in Hessen 14), Wiesbaden 1994.

Kingreen, Monica: Die gewaltsame Verschleppung der Juden aus den Dörfern und Städten des Regierungsbezirks Kassel in den Jahren 1941 und 1942, in: Das achte Licht. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte der Juden in Nordhessen, hrsg. v. Helmut Burmeister und Michael Dorhs, Hofgeismar 2002, S. 223-242

Kosog, Herbert: Die Juden von Roth, in: Heimatwelt (Weimar/Lahn), H. 5, 1979, S. 11-21

Neumann, Michael: Wir brauchen Denk-Räume. Zur Restaurierung der Synagoge von Roth an der Lahn (Kreis Marburg-Biedenkopf), in: Denkmalpflege und Kulturgeschichte 2, 1998, S. 2-4

Neumann, Michael: Erinnerungsarbeit. Denkmale jüdischer Vergangenheit, in: 25 Jahre Denkmalpflege in Hessen, hrsg. vom Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Hessen und dem Hessischen Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst, Wiesbaden 1999, S. 94-96

Neunhundert Jahre Geschichte der Juden in Hessen. Beiträge zum politischen, wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen Leben (Schriften der Kommission für die Geschichte der Juden in Hessen 6), Wiesbaden 1983

Poliak, Claudia: Die Arbeit des „Arbeitskreises Landsynagoge Roth“. Erinnern um der Zukunft willen, in: Jahrbuch für den Kreis Marburg-Biedenkopf 2008, S. 155-157

Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden im Hessischen Staatsarchiv Marburg 1267-1600, bearb. von Uta Löwenstein (Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden in hessischen Archiven 1), 3 Bde., 1989.

Rehme, Günther / Konstantin Haase: "... mit Rumpf und Stumpf ausrotten ...". Zur Geschichte der Juden in Marburg und Umgebung nach 1933 (Marburger Stadtschriften zur Geschichte und Kultur 6), 1982.

Richarz, Monika / Reinhard Rürup (Hrsg.): Jüdisches Leben auf dem Lande. Studien zur deutsch-jüdischen Geschichte (Schriftenreihe wissenschaftlicher Abhandlungen des Leo-Baeck-Instituts 56), 1997

Roth, Herbert: Die Juden von Roth (Kreis Marburg-Biedenkopf), aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Annegret Wenz, Manuskript 1987

Schlag, Annemarie: Artikel in der Chronik Von Essen nach Hessen. 850 Jahre Fronhausen 1159-2009, hrsg. von der Gemeinde Fronhausen, red. Renate Hildebrandt, Friedrich von Petersdorff und Siegfried Becker, Fronhausen 2009: Die jüdische Gemeinde in Fronhausen, S. 821-823; Der jüdische Betsaal in Fronhausen, S. 824-827; Die jüdische Elementarschule in Fronhausen, S. 827-830

Schmitt, Gabriele C.: Ehemalige jüdische Mitbürger und Nachfahren kommen nach Roth: 15-jähriges Jubiläum des Arbeitskreises Landsynagoge Roth, in: Jahrbuch für den Landkreis Marburg-Biedenkopf 2012, S. 217-220; textlich identisch, mit anderer Bildfolge in: Heimatwelt (Weimar/Lahn), H. 48, 2012, S. 3-7

Schmitz, Thomas: Alltag zwischen Bettel und Handel. Synagogengemeinde Roth war die zweitstärkste im Kreis. In: Oberhessische Presse 1983, Nr. 24 (Stadtausgabe).

Schüler entdeckten Mauerreste eines jüdischen Frauen-Bades. Die zehn Jugendlichen graben seit vier Tagen im Hof hinter der Rother Synagoge, In: Oberhessische Presse vom 13. Juni 1996

700 Jahre Roth. Dorfgeschichte in Texten und Bildern. 1302-2002, hrsg. v. Festausschuss 700 Jahre Roth, Marburg 2002

Treue, Wolfgang: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Marburg (Germania Judaica. Historisch-topographisches Handbuch zur Geschichte der Juden im Alten Reich, Tl. IV, 1520-1650), Tübingen 2009.

Versöhnung durch Erinnerungsarbeit (ohne Autor), in: Denkmalpflege in Hessen. Berichte 1997/1998, hrsg. v. Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Hessen, S. 43f.

Wagner, Barbara u.a.: Die jüdischen Friedhöfe und Familien in Fronhausen, Lohra, Roth, Marburg 2009

Weimar, Otto: Weimar präsentiert seine Gotteshäuser: In: Jahrbuch für den Kreis Marburg-Biedenkopf, Marburg-Biedenkopf 2008, S. 137-144; (Landsynagoge Roth, S.141)

Wenz-Haubfleisch, Annegret: Artikel in Die ehemalige Landsynagoge Roth und Gedenkstätte und Museum Trutzhain, hrsg. von Monika Hölscher (Hessische GeschichteN 1933-1945, H. 2), Wiesbaden 2013: Die jüdische Gemeinde in Roth, ihre Synagoge und ihr Friedhof, S. 2-6, Vom Holzdepot und Getreidespeicher zur Gedenk-, Lern- und Begegnungsstätte, S. 11-15; „Niemals schweigen gegenüber Hass und Diskriminierung“ – Lebensbeispiel Herbert Roth, S. 21-25.

Wenz-Haubfleisch, Annegret (Zusammenstellung und Redaktion): Stolpersteine für die ermordeten und vertriebenen Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger von Roth am 24. und 25. August 2013 – eine Dokumentation, in: Heimatwelt, H. 49, 2014, S. 37-48

Zippert, Christian: Erinnerung um der Zukunft willen. Ansprache anläßlich der Übergabe der wiederhergestellten Synagoge Roth an die Öffentlichkeit am 10. März 1998 (engl.: Remembrance for the Sake of the Future. Speech on the occasion of the opening to the public of the restored synagogue in Roth on 10 March 1998), hrsg. vom Kreisausschuss des Landkreises Marburg-Biedenkopf, Marburg 1998

Von der Ausgrenzung zur Deportation in Marburg und im Landkreis Marburg-Biedenkopf: Neue Beiträge zur Verfolgung und Ermordung von Juden und Sinti im Nationalsozialismus. Ein Gedenkbuch, hrsg. von Klaus-Peter Friedrich, Marburg 2017; darin: Annemarie Schlag, Fronhausen, S. 249-265, Familie Löwenstein in Oberwalgern, S. 383-385 Gabriele C. Schmitt, Die Briefe der Henni Höchster geb. Walldorf, S. 306-317 Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch, Roth an der Lahn, S. 161-185.

Photo: Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

Photo: Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

To those Jewish families who were expelled from Roth to other countries or deported and murdered during the Nazi era, the working group has dedicated stumbling blocks and a commemorative brochure with in-depth biographical information to 2010 and 2013.

Please use the pointes!

See the Pen CSS LED Lights by Eph Baum (@ephbaum) on CodePen.

In 2013, two families did not agree to the stones being laid in front of their properties. These nine stones were laid in front of the synagogue as a religious centre, with the actual address given, in the hope that they can be moved to their rightful place at a later date

by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

Foto: Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

Foto: Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

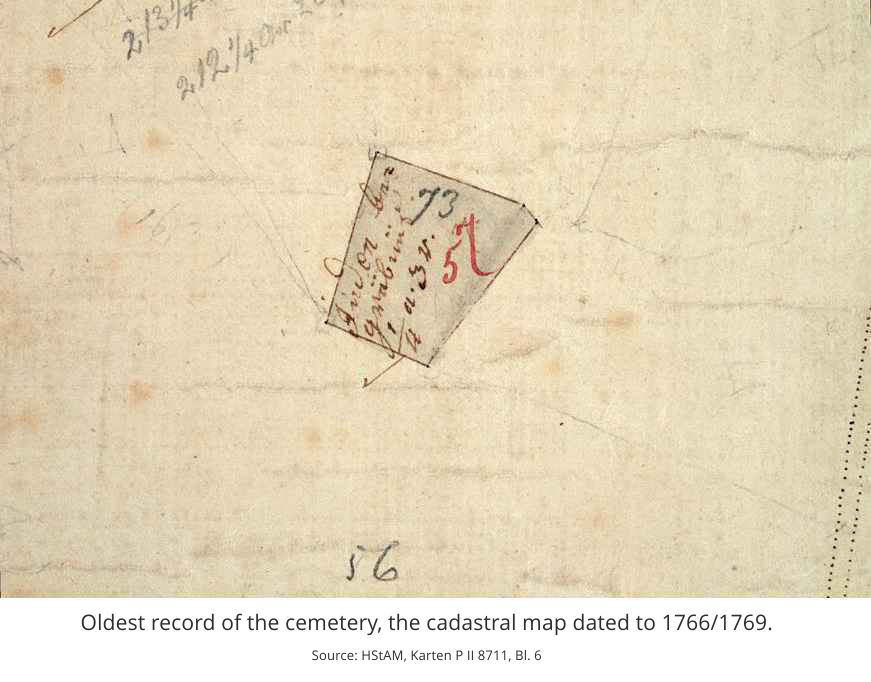

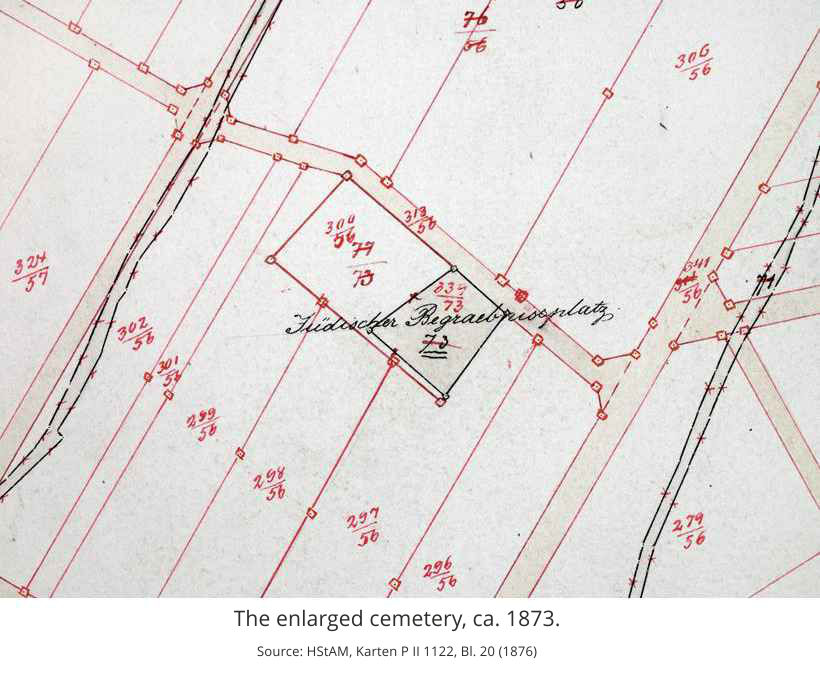

The first record of a Jewish Cemetery in Roth is found on a map from 1766/1769.

This map indicates the area of the Juden Begräbnüs (Jewish entombment) as having a size of ¼ Acker and 3 Ruthen (about 643 m² or 769 sq. yds.)

The cemetery was the only lot on an otherwise undivided piece of ground that was used as grazing land. The property owner listed in the relevant cadastre is the Village of Roth, meaning that the village owned the plot and merely allowed the Jewish Community to use the land. There are no gravestones remaining from this period. In the 19th century, the Jews from Roth, Fronhausen, and Lohra formed a single worship community and shared a synagogue and cemetery in Roth until the Jews from Fronhausen established their own cemetery on Kratzeberg in Fronhausen in 1873. At the same time, the Jews in Roth expanded their own cemetery to 1646 m² (1969 sq. yds.)

During the Nazi period many Jewish cemeteries were closed and secularized. In July 1939, the county commissioner in Marburg decreed that the Jewish cemetery in Roth should be closed. Thereafter deceased members of the Jewish Community were laid to rest in the collective cemetery in Marburg. The last Jewish person to be buried in Roth was Betty Nathan, née Stern, who died at age 81 on April 29th, 1939. She has no surviving gravestone.

The Jewish cemeteries began to be secularized in 1940. In Germany, for practical reasons of space, there is a time limit as to how long an individual grave may remain in a cemetery. This is called the Liegefrist or Ruhefrist. A Jewish cemetery must be granted an exception to this rule since the Jewish religion requires that graves are eternal: The site of a grave may not be leveled and used again.

Following the forced secularization of the Jewish cemeteries in 1940, the land of a cemetery was divided into three parts. The oldest part consisted of graves 30 years or older because thirty years was the length of the Liegefrist at that time. Graves older than 30 years had to be leveled for reuse. The second section consisted of land with younger graves. The third part was land that had been reserved for future burials.

The secularization of the cemetery in Roth was officially decreed in 1941. The three parts were sold to three adjoining neighbors. The part in which the Liegefrist was over was explicitly allowed to be leveled and the gravestones to be used for other purposes. Only special stones were to be saved.

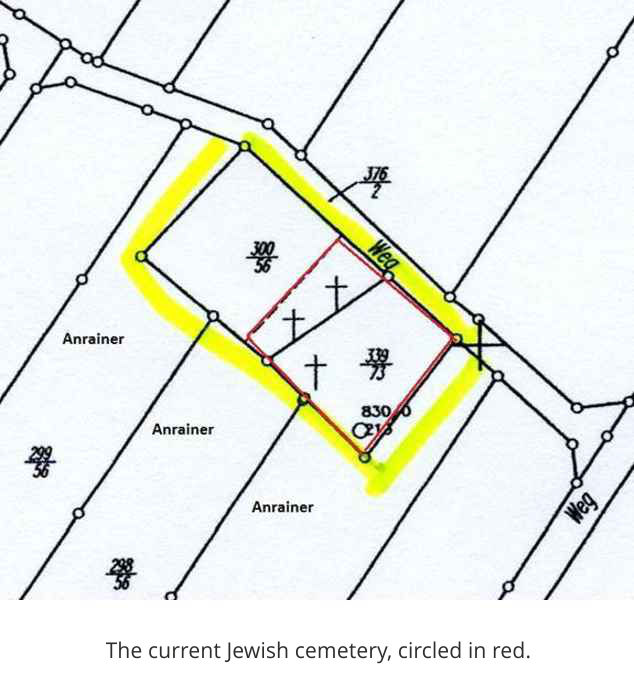

During the Nazi regime the gravestones were indeed taken and the cemetery desecrated. Otto Stern, who was stationed as an American soldier in Germany in 1945, visited his hometown and ordered the ravaged cemetery to be restored and newly fenced in. The Jewish Cemetery is now about 891 m² (1066 sq. yds.) in size. It has been in the possession of the Landesverband der jüdischen Gemeinden in Hessen (Association of Jewish Communities in Hessen) since 1960.

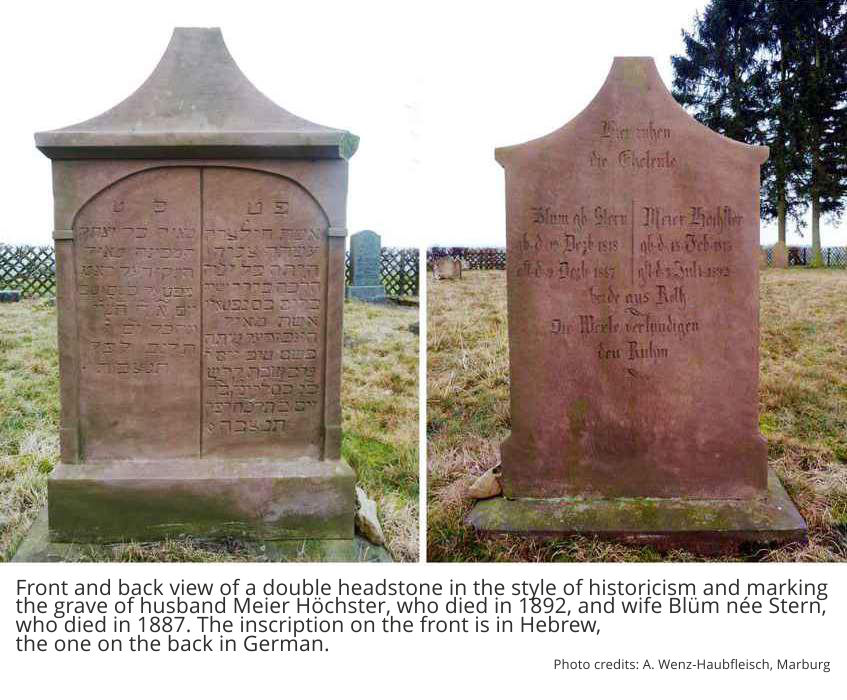

Today there are 43 original gravestones. Two new ones for Emma Stern and her daughter Selma Roth were laid in 1984. The oldest headstone, marking the grave of Anschel Löwenstein from Fronhausen, is from the year 1836. There is also a stone marking the grave of Herz Stern from Roth who died in 1844.

According to official records from the 19th century, at least 43 other burials took place in this cemetery. It is improbable that the gravestones still mark the original burial sites because they are not ordered chronologically, but rather according to family with large lapses of time between the dates of passing.

The style of the headstones is by and large very simple. There are few ornaments, and the letters are usually engraved rather than raised in the stone. The main inscription is usually in Hebrew, and it is set within a carved round arch. Occasionally a headstone has two carved arches resembling the Tablets of the Ten Commandments. At the end of the 19th century, we find elements of historicism such as the depiction of a roof carried by two pillars.

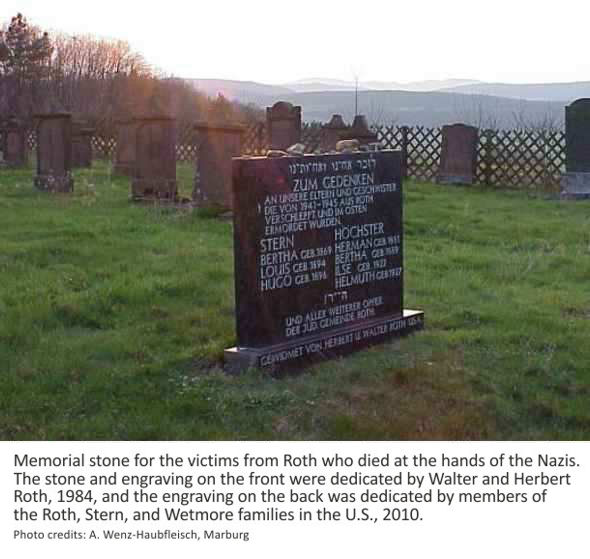

In 1984, Herbert and Walter Roth, two brothers who had been able to escape to the USA, dedicated a monument to the memory of the parents and siblings of the Stern and Höchster families who had been deported to concentration camps and then murdered there between 1941 and 1945.

With donations from the next generation, the names of the murdered members of the Bergenstein and Nathan families could also be added to the back side of the memorial stone in 2010.

The cemetery was desecrated again in early January 2012. Four headstones were knocked over and 16 were vandalized with purple satanic crosses as well as one swastika. The Arbeitskreis Landsynagoge Roth (The Society for the Rural Synagogue in Roth) held a vigil in defiance of these actions on January 15th, 2012. Approximately 300 people built a human chain around the cemetery.

All pictures: Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

Lageplan von B. Wagner in: Wagner, Barbara u.a.: Die jüdischen Friedhöfe und Familien in Fronhausen, Lohra, Roth, Marburg 2009

The Roth cemetery is located far outside the village on the "Geiersberg" high above the Lahn valley.

The Jewish cemetery is located on a hill, the Geiersberg, to the south of Roth. It can be reached via the streets Am Heier or Buchenweg.

by Annegret Wenz-Haubfleisch

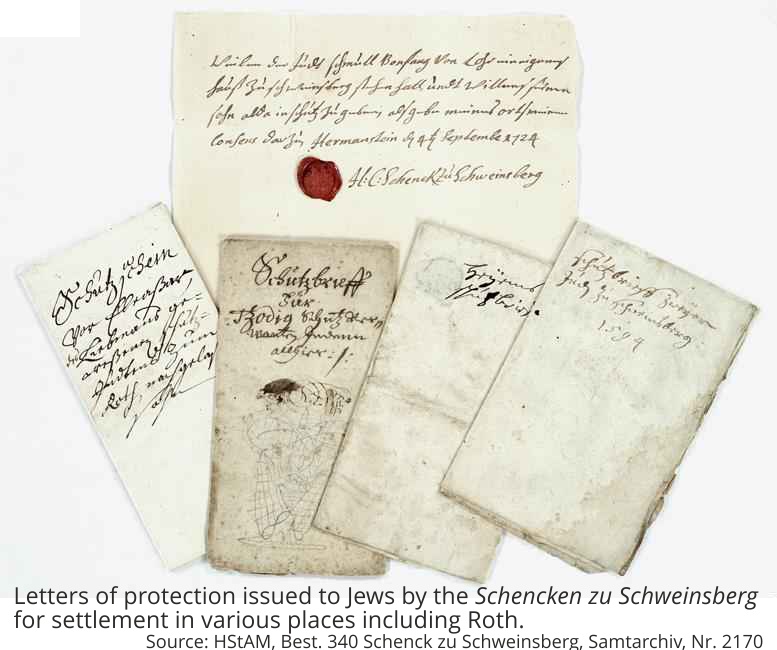

The villages of Roth, Wenkbach, and Argenstein once made up the Schenkisch Eigen, a set of lands under the sovereign control of the noble lineage Schenk zu Schweinsberg. This ancient noble family possessed extensive rights over this territory, including the right to settle Jews on the land. They did this by selling Schutzbriefe (letters of protection) to persons of Jewish faith, a lucrative source of income.

Early evidence of Jews living in the Schenkisch Eigen is found in a 1594/95 register of taxes levied for military protection against the Turks. According to this source, there were seven Jews living in the area who had to pay taxes on property worth 200 Gulden. Each of the seven had to pay 3 ½ Heller for defense against the Turks. It is probable that some of the seven Jews and their families lived in Roth.

There is definitive evidence from the year 1666 that four Jewish families were living in Roth. In 1710 there were six Jewish families with a total of 33 people. By 1737 the number had grown to 13 families with 54 people. In 1744 the Landgrave of Hesse began to intervene in the settlement of Jews in the villages and towns under his control. He had a register made of all the Jews living in his domain, which included the names of each person in the family. He then decided who would and would not be granted further right of abode in which place. As a result of this action, most of the ca. 38 people (nine families) living in Roth lost their right to live there. Only two families were allowed to stay. After this, the Jewish Community in the area remained very small for several decades.

It was not until the time of Napoleon’s brother Jérôme’s rule in the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807-1813) that the Jews were first awarded equal standing as citizens. Jews from outside Roth married into the community and paved the way for demographic development in the 19th century. By 1816, a total of four families were again living in Roth: Bergenstein, Höchster, Stern, and Wäscher. By the middle of the century the number of families doubled. The younger sons of the four main families stayed in Roth, and a new family with the surname Nathan arrived in the village. At that time there were about 50 Jews living in Roth, and they made up about 10 percent of the population. By percent Roth had one of the largest Jewish communities in the area around Marburg. When Hitler came to power in 1933, there were still six families in Roth: Bergenstein, Höchster, Nathan, Wäscher, and 3 families with the surname Stern, a total of 32 people.

The Jews of Roth, Fronhausen, and Lohra formed a single worship community in the 19th century. By the middle of the 18th century, they had a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery in Roth.

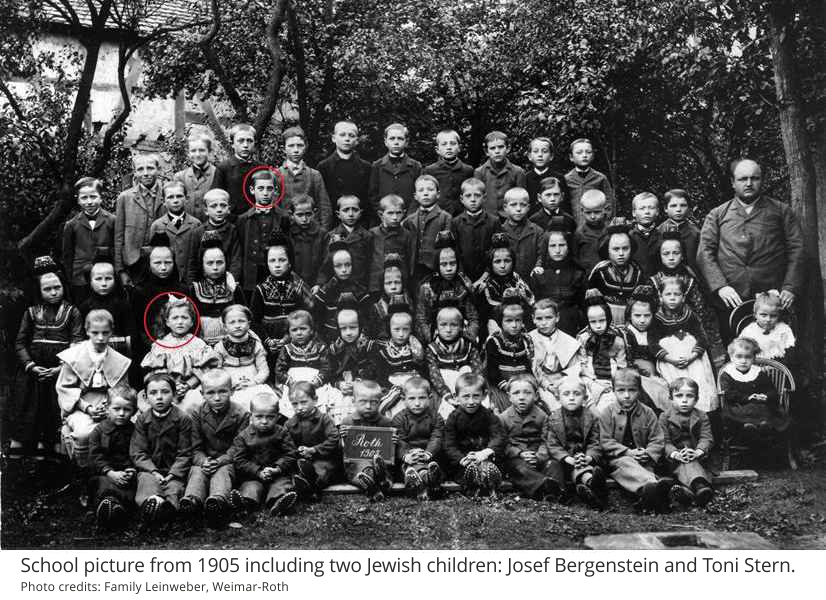

A Jewish elementary school was also established. The schoolteacher usually lived in Roth, but also had to give lessons in Fronhausen for the children from Fronhausen and Lohra. It hasn’t been possible to locate where the school in Roth used to be. The Fronhausen Community split from the larger community in 1881, and bought a building for use as a prayer-house and Jewish school. The Jewish children in Roth began attending the public school at this time.

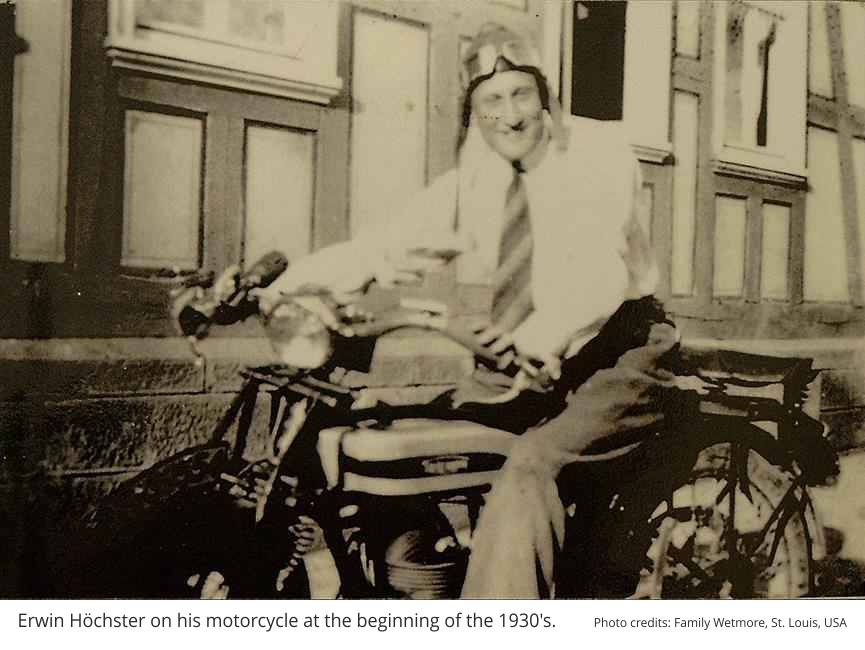

As was typical for Jews in rural areas, the Jews in Roth earned their living through trade, usually dry goods, notions, and fabric or grain and feed, as well as livestock. Well into the 20th century, they traveled the countryside, either by horse and cart, by foot with a Saint Bernard and a small wagon, or eventually by motorcycle, selling their wares. Some Jews owned land and livestock and ran small farms.

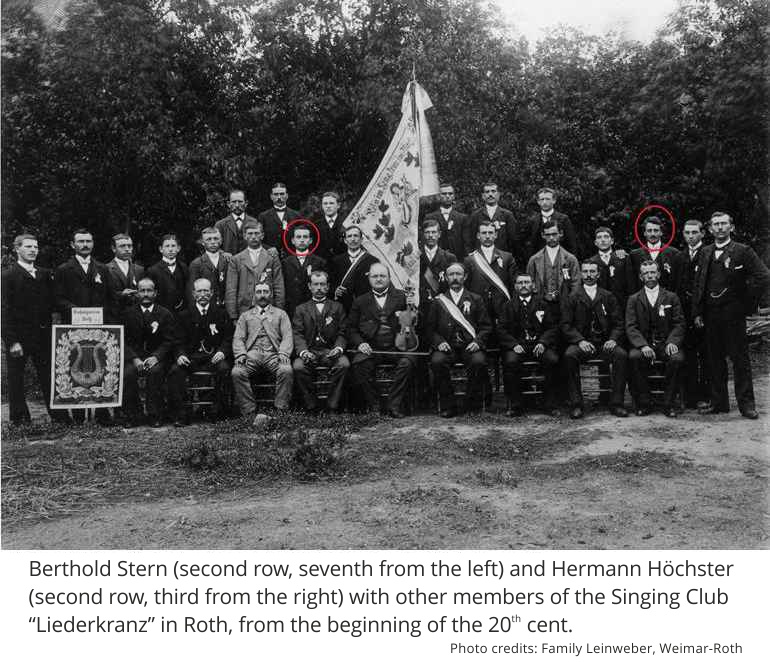

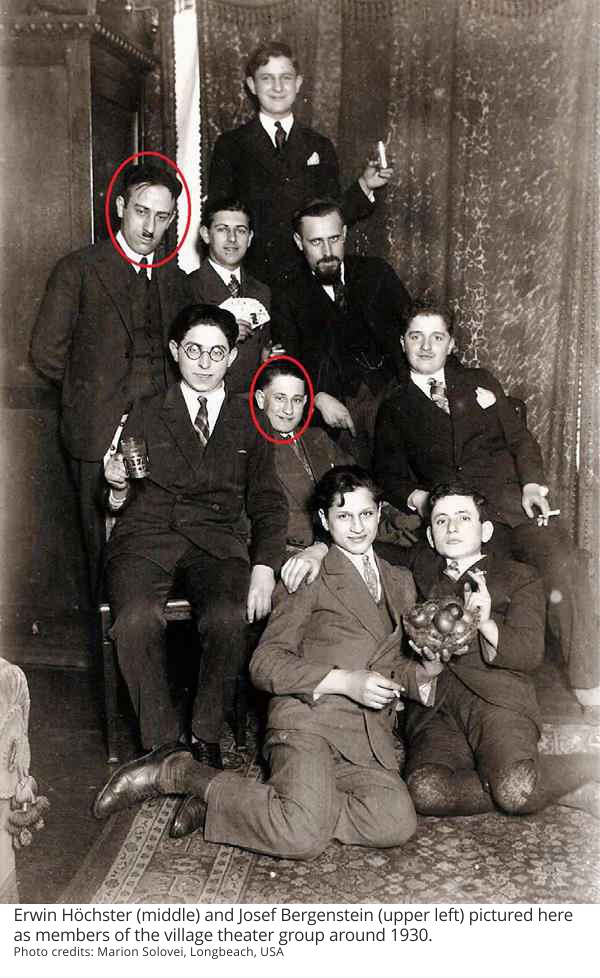

Around the end of the 19th century, members of the Jewish community began joining the local athletic and choir clubs so popular among the general population at this time. There were also Jewish members of the local theater group in Roth. This involvement indicates the extent to which people of Jewish faith were integrated in the village community. Contemporaries bear witness to the positive neighborly relations between Jews and the rest of the population in the 1920’s. Christian and Jewish children played together and formed friendships.

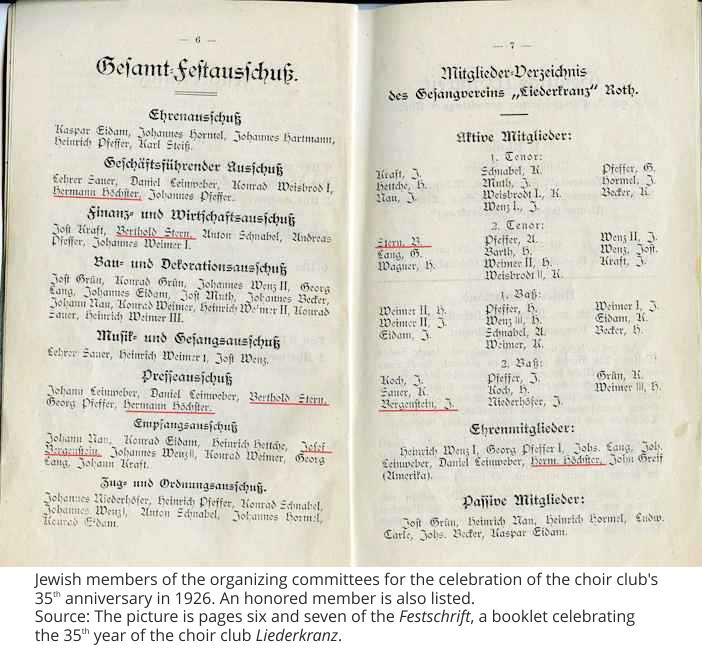

Records of the 35th anniversary of the local choir club, show no evidence of ostracism or exclusion by either side in 1926. The Festschrift, a booklet serving as a memorial document marking the occasion, includes men from several Jewish families as members of the club. Some of these men were involved in the festival committees. Hermann Höchster, the Jewish community elder, is listed as an honored member of the club.

The historical election results from the time of the Weimar Republic indicate that Roth was not particularly “brown” - the Nazi Party received fewer votes than the district average between 1928 and 1932. However, the situation changed very quickly after Hitler came to power.

A young mother named Selma Roth died suddenly in 1934. According to members of her family, many villagers attended Selma’s funeral; however, it was only one year later that her widower, the fertilizer dealer Markus Roth, was denounced and accused of criminal behavior in court. Roth’s business collapsed in the aftermath. Signs stating “Juden sind hier unerwünscht” (in English: “Jews are not wanted here”) are documented as having been on a business property and on a farm at this time.

Survivors report of nasty pranks and of being excluded from play at school after the Christian children joined the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) and the Bund deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls: the girls’ branch of the Hitler Youth.) Adult Christians began avoiding their Jewish friends and neighbors. Jewish men were not allowed to work and thus could no longer support their families. Jewish families began to see that there was no future for them in Germany. They tried to flee, but not all of them had the financial means and necessary contacts to emigrate. Some members of the Höchster, Roth, and Stern families managed to escape between 1936 and 1938, but only one of the two Stern families was able to flee as a complete unit. Eleven Jews from Roth survived in South Africa, the USA, and in England.

For those left behind, life became increasingly difficult as laws and regulations became stricter and economic hardships ever more pressing. To make matters worse, Roth served as a ghetto village in the summer of 1941. At that time, many Jews were forcibly concentrated into single houses in the cities and centralized places in the countryside. Twenty Jews from Neustadt were forced to moved into living quarters with the remaining members of the Bergenstein, Höchster, Nathan, and Stern families. They lived there in terribly tight conditions. Some of the Jews were deported to Riga in December 1941, the rest were deported to Theresienstadt in September 1942. None of the Jews from Roth survived the ghettos and the concentration camps.

Jewish life in Roth was thus completely exterminated.